A Time for Silence

Encountering Wounded Knee

A Bad Morning

The morning drive had become unpleasant, then disorienting.

We were finishing the first week of our road trip. The day before, South Dakota's Badlands hit 100 degrees. When I turned on the air conditioner mid-morning, it blew nothing but hot air. My spouse took a business call, while I drove on, fuming and sweating; it was not close to noon yet. Next, the road signs indicated we were not on the route I'd planned, having apparently missed a turn while fiddling with the failing AC. Nothing about this day seemed to be going right.

Hot and exasperated, I pulled over to a parking lot at a crossroads to get my bearings. In front of me, a historic site that stabbed through the decades: Wounded Knee Creek.

"Simply Went Berserk"

In 1890, across the West, Native Americans participated in the Ghost Dance, a millennialist religious movement inspired by Wovoka, a Paiute, that promised a return of the old ways and the disappearance of white people.

The Ghost Dance represented many things, including an assertion of autonomy and a rejection of the assimilation program imposed by force by the US government. It alarmed the military, which sent between 6,000 and 7,000 troops to surround the Lakota in the largest military mobilization since the Civil War.

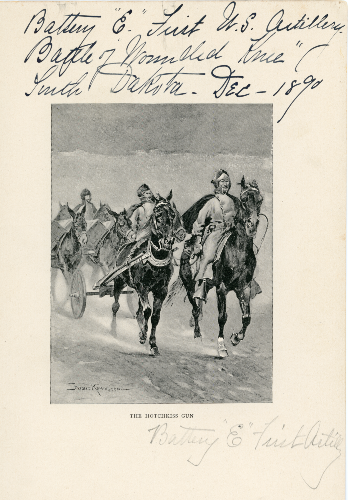

One group of Minneconjou, led by Big Foot, headed to Pine Ridge where they hoped Red Cloud might broker peace with the Army. The Seventh Cavalry (Custer's regiment) stopped them and gathered them at Wounded Knee Creek. Under a truce flag, the Army disarmed Big Foot's men. Black Coyote, a deaf elder, perhaps confused, refused to relinquish his weapon; it—or another—weapon fired. Then, the cavalry began an unrelenting massacre, firing Hotchkiss cannons and chasing down escaping women, children, and men.

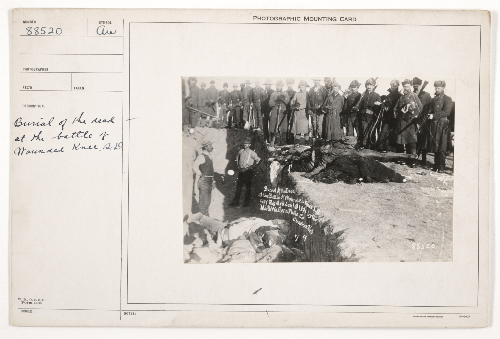

The numbers remain disputed, but perhaps as many as 300 were killed, only 100 were men.

One witness, Private Hugh McGinnis, said, "Judging by the slaughter on the battlefield it was suggested that the soldiers simply went berserk. For who could explain such a merciless disregard for life?"

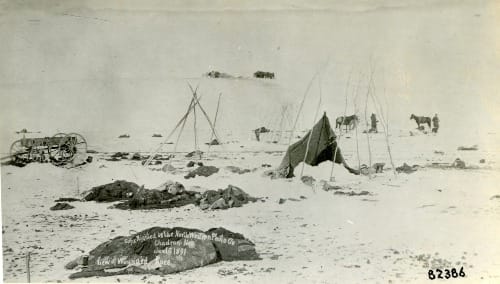

Charles Eastman, a Santee Sioux doctor who aided survivors, reported, "Fully three miles from the scene of the massacre we found the body of a woman completely covered with a blanket of snow, and from this point on we found them scattered along as they had been relentlessly hunted down and slaughtered while fleeing for their lives." The massacre tested Eastman's new Christian faith and Americans' claims to civilization.

Black Elk, a Lakota holy man, recalled seeing people "heaped and scattered all over. . . . The dead women and children and babies were scattered. When I saw this I wished that I had died too."

Twenty-five soldiers died, most likely from their own crossfire. A blizzard swept the land, but after three days, General Nelson A. Miles arrived to observe the site firsthand and was shocked. He relieved Colonel James W. Forsyth of his command and investigated friendly fire and the deaths of noncombatants. In a private letter, Miles said, "I have never heard of a more brutal, cold-blooded massacre than that at Wounded Knee." He also called it "the most abominable military blunder and a horrible massacre of women and children."

Publicly, Miles cleared the soldiers of wrongdoing.

Post-Script Politics

On the 100th anniversary of this massacre, in a Concurrent Resolution, Congress acknowledged the "tragedy." It pegged the number of deaths and casualties at between 350 and 375. It expressed "deep regret." Finally, Congress shared "its commitment to acknowledge and learn from our history, including the Wounded Knee Massacre, in order to provide a proper foundation for building an ever more human, enlightened, and just society for the future."

Two years later, Congress authorized a Chief Big Foot National Memorial Park and Wounded Knee National Memorial. The bill found that under a truce flag, almost all that were killed or wounded "were unarmed and entitled to protection of their rights to property, person and life under Federal law." It again asserted Congress' commitment to learn from history.

We are, however, failing.

Last week, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth affirmed that soldiers at Wounded Knee who had been awarded the Medal of Honor would keep their medals. Last year, Hegseth's predecessor, Lloyd Austin, ordered a review but made no decision. In his announcement, Secretary Hegseth referred to the Battle of Wounded Knee, a mocking misnomer of the massacre, and he praised the soldiers' bravery while emphasizing that they deserved the recognition.

Stillness

Studying American history prepares you to encounter the lingering presence of the past. But I was not prepared for Wounded Knee Creek.

For a week, I had freely photographed anything remotely interesting, hopping out of our van to capture multiple images. Landscapes. Interpretive signs. Wildlife. Campsites. Here I couldn't move. Our worst day on the road with the only real problem we faced on the 5,000-mile trip brought us to a place of unspeakable tragedy.

Armed with historical understanding, I often feel immunized from surprise. But then there are moments like this one where the weight of a place and what happened at it squeezes and immobilizes me.

Some places, like Wounded Knee Creek, deserve their stillness and solemnity.

Comments ()