Capturing the Scene

Photographer John K. Hillers and the complexity of picturing the West

In 1871, a German immigrant working as a teamster in Salt Lake City had a chance meeting that changed his life. The historical record that emerged from that encounter is consequential, evocative, and challenging.

John Wesley Powell, a government surveyor who led the first expedition down the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon in 1869, needed to fill out his crew for the second expedition. Most of the group was already gathered, and most of them had earned their positions through nepotism of one sort or another.

The immigrant teamster, John K. "Jack" Hillers, did not join because of anyone he knew. Powell needed a replacement for a crew member who could not join, and Hillers was, according to Powell’s biographer Donald Worster, “big, strong, and agreeable.” Being at the right place at the right time with the right qualities sometimes beats out who you know.

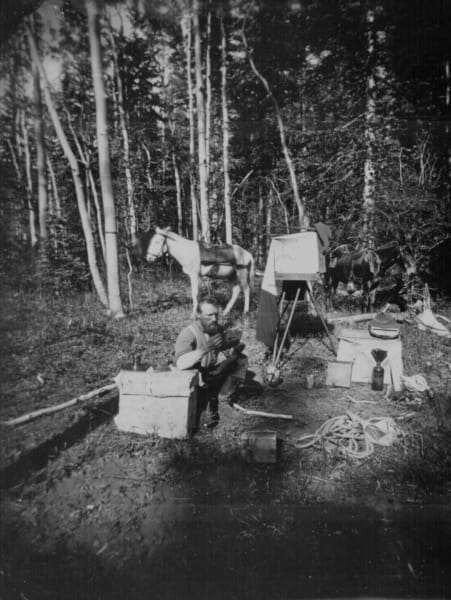

Hired on as a boatman, Hillers quickly became the photographer’s assistant. He showed a knack for it and acquired “distinguished competence the hard way, in the field,” in the words of Wallace Stegner, another Powell biographer.

All that photographic work occurred “under impossibly laborious conditions,” wrote Stephen J. Pyne in How the Canyon Became Grand. Consider the terrain and equipment necessary for a 19th-century camera and it seems miraculous any photographic plates made it from the Colorado Plateau to Washington, D.C.

When Powell’s survey ended, Hillers continued working with him for decades on the Colorado Plateau and in the nation's capital, working for the Bureau of American Ethnology and the U.S. Geological Survey.

Hillers is hardly a household name, even among western historians, but Worster wrote that the photographs he took constituted some of the most valuable records of the survey. For historians, Hillers’s photos open windows into the past that can beguile.

At least they did me. Last week, looking for illustrations for my essay, I encountered a cache in the National Archives of more than 500 photos from his time working for Powell. I've been thinking about them and looking at them (and others) ever since.

Many western expeditions brought artists and photographers to provide evidence of landscapes and people. Readers at the time understood photographs to be more straightforward, less manipulable than the paintings and wood engravings used to illustrate reports, popular articles, and books.

In the convention of this time, photographs furnished facts while the other forms fueled emotional responses.

In fact, Hillers’ photos from the survey provided inspiration and reference to the artists and writers who found themselves in the Powell expedition’s orbit, such as Thomas Moran, one of the nation’s most celebrated landscape painters.

Moran and others consulted the images while creating their own art. They had their own sketches, of course, but artists and writers perused Hillers' pictures – much like I have – looking for details and finding inspiration and reminders. So even when looking at these century-old documents that never mention Hillers, his influence is just beneath the surface.

Just as 19th-century photography served science, it also served commerce, or at least filled some funding gaps, which complicates any assessment.

Although they were important and yielded valuable information, scientific surveys were not the top priority of Congress. Powell used the sale of images to help finance his activities when public purse strings tightened.

Worster called Powell and his photographers, namely Hillers, “artistic entrepreneurs.” Powell arranged for Hillers to earn 40% on sales of images, while Powell prepared 650 images for sale.

Stereographs were the most lucrative. These were dual images that would provide a type of three-dimensional view when look at through a stereoscope. This plan paid off. In the first six months of 1874, they earned a reported $4,100, an equivalent of around $115,000 today.

The previous year, during the Panic of 1873, Hillers had to take a temporary unpaid leave and live with the Powells. The attractiveness of selling western images comes into focus.

And it is not hard to see why such images attracted audiences. These landscapes would have seem wild and unfamiliar – even disorienting – to the audiences in the East listening to lectures. But also enticing.

The photographs shout the landscape’s ancientness. The power of erosion accumulating over millennia is plain in every canyon view and each glimpse of sandstone worn down.

Eroded Supai Sandstone on Kaibab Plateau; Grand Canyon from the north rim looking at Prospect Canyon and Lava Falls Rapids, 1873. (National Archives)

While the landscapes suggest an almost endless passing of time at the slowest pace, Hillers took hundreds of photos of Indigenous peoples and their homes that evoke something nearly the opposite.

Scanning through hundreds of Hillers’ photographs in the Smithsonian Online Virtual Archives, you will find a range of photos. Some capture diverse Colorado Plateau cultures’ lifeways borne out of generations of practice living in place; some capture staged images designed for white audiences and their prejudices; some capture portraits of individuals wearing suits to reflect new pressures. Hillers’ career spanned a transformative age.

Neither Hillers nor Powell offered compensation to those who they photographed, a type of extraction all too common in this history.

Zuni Pueblo, 1879. (Bureau of American Ethnology

The photos Hillers took of pueblos and homes especially grab the imagination, but an uneasy feeling of voyeurism arises.

The photographs Hillers left as a historical archive raise questions and inspire imagination.

For residents or travelers in the region he portrayed, Hillers’s photos encourage exploration and comparison. For those whose homelands and ancestors are depicted in idealized and romanticized ways the archive is far more complicated.

This is a common historical dilemma. The past exerts an inexorable pull on our curiosity, but the more details that emerge, the more complicated the past becomes. Our task in that moment is to resist simplicity.

Comments ()