Common Ground in November

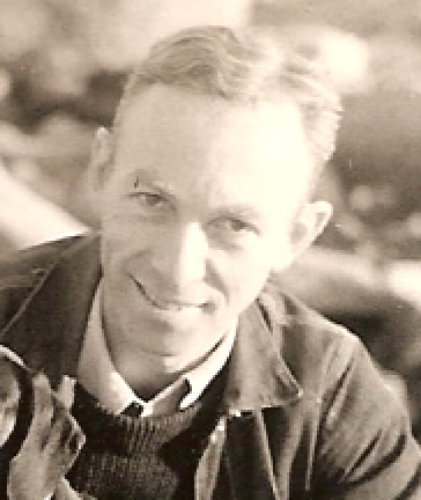

E. B. White in his time and ours

One week in November—close enough to Thanksgiving to smell cranberries—the writer E. B. White (1899-1985) described a typical week on his farm for the readers of his regular Harper’s column, “One Man’s Meat.” This particular week occurred just eleven months after the attack on Pearl Harbor. White’s Maine farm showed signs of the war; his prose showed signs of his wisdom.

White was neither an ordinary writer nor farmer. He had helped define the New Yorker’s style. Then, in 1938, waist-deep in the Great Depression, White left the city and settled into his country house to raise food and write in fresher air.

The experiment suited White. He learned through trials and lots of errors how to raise food; he learned through trials and lots of revisions how to write exquisite essays that somehow centered on simple everyday occurrences and revealed grand visions of a humane world.

White moved to Maine full-time in the Depression and by the time his essay “A Week in November” appeared in 1942, World War II hung over everything. In such times, a citizen’s responsibility had ways of revealing itself.

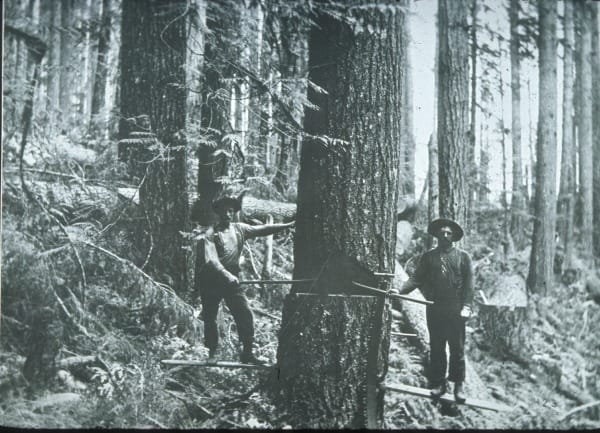

White’s move to Maine had preceded the war and the need for Americans to be more self-sufficient and contribute to the war effort. But once it began, he mobilized the farm. The writer and neophyte farmer set hefty goals for 1942-43:

- 100 pounds of wool,

- 14 lambs,

- 4,000 dozen eggs,

- 10 spring pigs,

- 150 pounds of broilers and roasters, and

- 9,000 pounds of milk.

This tally included none of the vegetables and fruits he raised for his own consumption and canning. A large-scale farmer might scoff, but White judged “it is about right for a half-time worker when labor is precarious and implements and materials are hard to get.”

All the while he prepped his fields and repaired outbuildings, his rural neighborhood depopulated. Young men joined the armed forces. Others moved to cities to work in factories. That left room for civic involvement.

On Friday, he and his wife Katharine (Angell) White (a New Yorker editor and writer) spent four hours looking for bombers from the “spotting post” in the abandoned local schoolhouse.

White seemed happy enough to watch for invading, or friendly, planes. Love of country and democracy beat fervently in White.

Yet the war also unnerved him; he was too much a realist for it to be otherwise. “There are two distinct wars being fought in the world,” White declared. One was real, “bloody and terrible and cruel, a war of ups and downs.” The other was imaginary, “the personal responsibility of the advertising men of America” which is a “lovely thing” because in this war the United States is “always winning . . . and the paint job stays bright on the bombers.” The ad-men imagined themselves heroes, the center of the story.

Responsibility of citizenship demanded more, White seemed to say. Picture him ruminating about this during his hours tending the animals who were always getting sick or getting out or getting into mischief. He understood responsibility.

The farm reframed his attention and priorities.

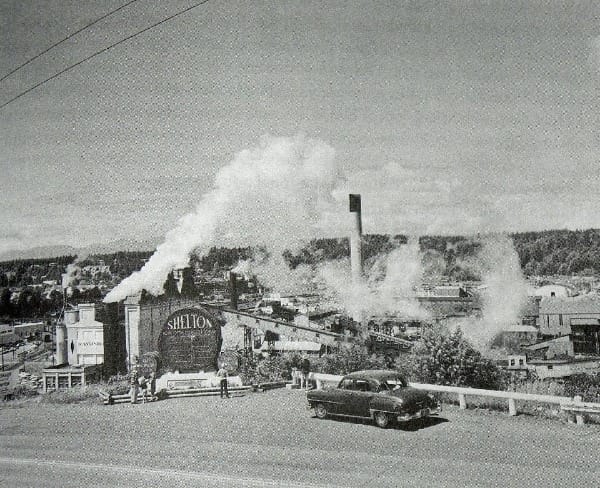

White anticipated a new day was coming for property owners. In his time, all owners had to do was pay the mortgage and keep up with the taxes (no mean feat during the Depression, of course). Beyond those bare minimums, they could turn a hayfield into a gravel pit; they could erode hillsides with no regard for neighbors; they could cut down a forest; they could build whatever kind of building they’d like “in the shape of a square or an octagon or a milk bottle.”

White knew that kind of freedom let us down, and he was not alone. Some of his contemporaries suspected “that the greatest freedom is not achieved by sheer irresponsibility.”

Instead, White wrote of something greater:

The earth is common ground and we are all overlords, whether we hold title or not; gradually the idea is taking form that the land must be held in safekeeping, that one generation is to some extent responsible to the next, and that it is contrary to the public good to allow an individual, merely because of his whims or his ambitions, to destroy almost beyond repair any part of the soil or the water or even the view.

His years working the farm had changed White, and he thought that after the war, Americans needed to move to the country. An equilibrium had been disrupted. Taking care of our own wants, “whether it be a sweet pea or a sour pickle,” would rebalance the citizenry.

White’s vision has not happened, yet.

For this week in November, on the occasion of Thanksgiving, I invite us to think about our own responsibilities as citizens or neighbors or family—that is, as a people among others on the earth, not as individuals alone in space—and channel our inner E. B. White and see how common responsibility outweighs individual ambitions. May we look beyond the quick hits and rosy images of ad-men and influencers and follow the generosity these times demand.

I have written about E. B. White before and Thanksgiving, too, if you find yourself with extra time to read this week.

Comments ()