Defining Outdoor Recreation

How to think about recreation in the 1920s

The president made an uncharacteristic announcement on April 14.

“Particularly within the last decade, the outdoor recreation spirit among our people has increased rapidly,” he said, despite not being well-known for interests in either the outdoors or recreation.

He continued:

During this period there have been put forward projects — federal, municipal, state and private — to expand and conserve throughout the country our recreational opportunities. . . . The physical vigor, moral strength and clean simplicity of mind of the American people can be immeasurably furthered by the properly developed opportunities for the life in the open, afforded by our forests, mountains, and water-ways.

The president noted that concern about access to recreational possibilities affected everyone, and the federal government, with its national forests and parks and wildlife refuges, needed to play a central role in promoting and managing the opportunities available.

Of course, I’m talking about Calvin Coolidge in 1924 — a surprise, although not quite as surprising as if the words had come from the current president.

Context

The period just after World War I reoriented Americans’ relationship with the outdoors, something explored well in Paul Sutter’s Driven Wild: How the Fight against Automobiles Launched the Modern Wilderness Movement (2002).

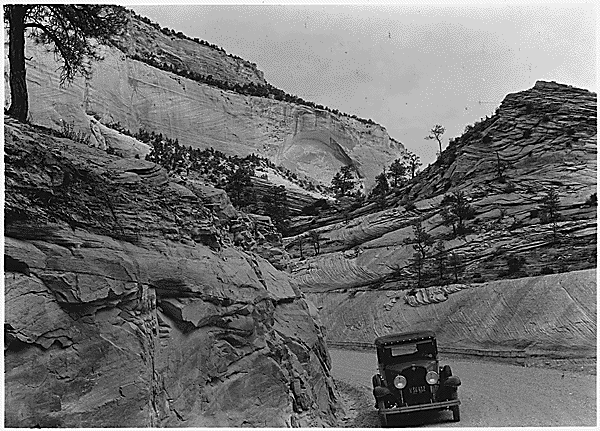

Technology explains much of that. The broad affordability of automobiles allowed more and more Americans to travel into mountains and deserts to experience unusual landscapes comparatively unmarred by industrial production.

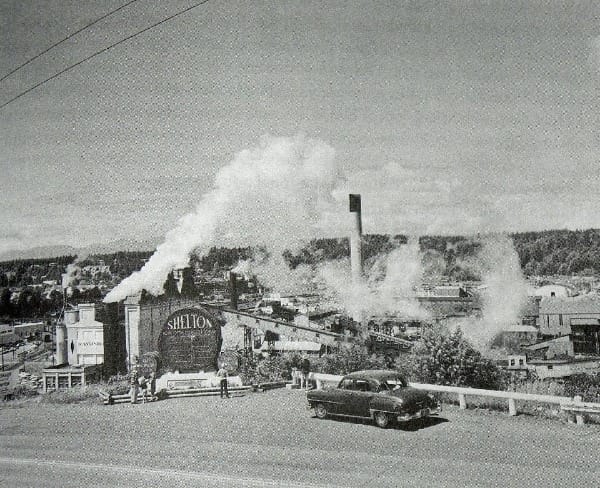

That industrialization and its associated urbanization relied on new technologies, too. Their byproducts for labor concerned many Americans, who found factory work and middle-class tasks to threaten traditional roles. The nation had long believed so-called country life to be the most virtuous, which was more an ideology than an accurate description of reality.

Wholesome outdoor recreation — like camping trips to the backcountry to see wildlife and exceptional scenery — would counter polluted cities and the growth of jobs where vigorous labor was no longer a requirement.

This was the context for Coolidge’s National Conference on Outdoor Recreation that he convened 101 years ago this month. Nationalism ran through it all, from a celebration of American scenery to a sort of martial vigor typically associated with military preparedness, along with more typical preservationist sentiment toward wildlife and majestic landscapes.

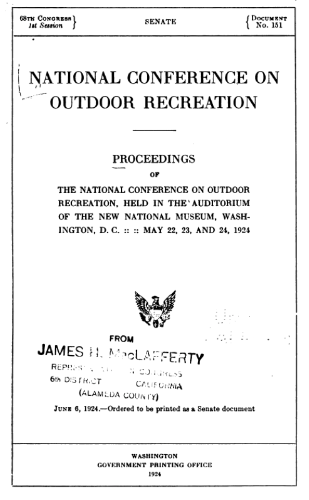

National Conference on Outdoor Recreation, 1924

NCOR lasted for three days and was held in the auditorium at the National Museum, now known as the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. Coolidge and those he appointed to coordinate the conference aimed to promote cooperation among governments at multiple levels and between them and other organizations and businesses, a common approach of 1920s governance sometimes called associationalism. Perhaps policy recommendations might also be developed at the gathering.

In his opening remarks, Coolidge claimed that “one of the ideals of perfection has been that of a sound mind, in a sound body.” In generations past, “an active outdoor life in the open country” was a “universal custom” among Americans. Coolidge and others like him sought ways to replace this among a populace where it had become less common.

Coolidge’s comments meandered a bit — not surprising perhaps for someone nicknamed “Silent Cal” for his reticence to speak. He praised the outdoors and developments meant to promote recreation, but he spent time talking about playgrounds and polo and football more than national forest trails. Given the others who attended and their abiding interests (not to mention what we associate with “outdoor recreation” today), Coolidge’s focus seemed off.

An Incubator

The reason I know of NCOR is because it played a role in nurturing a group of people interested in developing a wilderness policy. In Driven Wild, Sutter tells the story of four of the people who, in the interwar period, came together to form the Wilderness Society. Two of them — Benton MacKaye and Robert Sterling Yard — spoke at the conference. A third, Aldo Leopold, wrote in Sunset Magazine the following year that “the most needed move” to prevent the “steam roller” from winning and destroying remaining wildlands was “to secure recognition of the need for a Wilderness Area Policy from the National Conference on Outdoor Recreation.”

In other words, NCOR incubated important ideas.

It was not just wilderness, of course. Concerns about wildlife drew many luminaries to the conference, such as John C. Merriam and William Hornaday. Others represented scientific institutions, hunting and fishing groups, and a variety of other types of organizations ranging from the American Historical Association to the Colored Civic League of New Orleans to the United Spanish War Veterans.

This diversity reflected the nation, at least a bit. It also indicated that “outdoor recreation” in 1924 still was in the process of definition. In such moments the historical record captures possibilities more than certainties, bigger tents rather than small cliques. The time experienced great change and challenge, and groups we later would see as strange bedfellows — wilderness advocates and the PTA? — gathered together to share ideas, experimentally and hopefully.

Permanence vs. Diminishment; 1924 vs. 2025

When NCOR issued its resolutions, it started with citizenship and moved quickly to federal land policy. Its first resolution, stilted construction and all, captured much:

That the Conference express its approval of the historic and popular belief that the National Parks System consists of permanent national reservations protecting inviolate those wonderful or unique areas of our country which are museums representing the scenery and principal natural features of the United States available in our great heritage of animate and inanimate nature.

That historical vision of permanence is refreshing. Especially looking back from 2025.

For those of us who are committed to the public lands in the United States, recent headlines are worrying. News often centers on privatizing federal lands, transferring parks to the states, and cutting the National Park Service budget by 25%. Each one of those items is alarming; more bad proposals will be forthcoming.

Consistency, much less stable rationale, is not a hallmark of the current administration, of course. So it is never clear whether celebrating national greatness or undermining it will win.

When he declared National Park Week on April 23, President Trump celebrated the more than 400 national park sites. The budget he put forth a week later, though, said some of those sites don’t count and should be given to the states, a surefire way to diminish them.

These cuts and proposals to hollow out the national park and public land system goes against the values of the American public and the historical Republican Party. Even as odd a figure as Coolidge, representing a very conservative and pro-business Republican Party, understood that our outdoor heritage belonged to the nation forever.

In Other Words

- Conferences like this are not uncommon. I’ve written before about a major conservation conference from 1908 and one from 1962:

Comments ()