Elitism and Refuge in America's Breathing Spaces

Exploring the paradoxes of Acadia National Park

The moment the sun rises on the United States, it touches a national park. It's hard not to read something deeply symbolic in this. After all, President Franklin D. Roosevelt once said, "There is nothing so American as our national parks."

I might quibble with Roosevelt's sentiment. Plenty of things seem at least as characteristic as beautiful scenes and historic sites—many of them quite unsavory. But in their aspirations, national parks do reflect some of the best American impulses.

That national park that received a new day's first sunlight is Acadia, and yesterday marked the 109th anniversary of the park's first day with federal protection. It's a timely moment to consider its distinct history that stands apart from the better known western parks like Glacier or Crater Lake but otherwise connects to common national park themes.

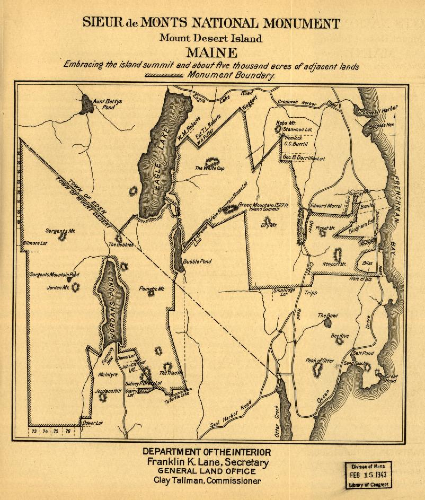

Acadia has had three names while under federal management: Sieur de Monts National Monument (1916-19), Lafayette National Park (1919-29), and Acadia (1929-present). This shifting nomenclature might suggest a confusion in mission or fit in the system. However, an old story lurks in this history.

The earliest national parks were marked by what historian Alfred Runte called monumentalism: glacier-carved valleys (Yosemite), hulking mountains (Mount Rainier), unusual geysers (Yellowstone), deep canyons (Grand Canyon), enormous trees (Sequoia). By any reasonable measure, these were scenically stunning and vast in scale.

By contrast, Mount Desert Island off the Maine coast hardly seemed to qualify. Its high point barely pokes above 1,500 feet in elevation. Since scale seemed comparatively modest, advocates for this place emphasized contrasts. The way rugged island mountains met the ocean had no parallel.

Robert Sterling Yard, the quintessential publicist for the early national park system who worked hard to establish standards for the parks, allowed that Acadia was "the only spot on our Atlantic coast where mountain and seashore intimately mingle." Nowhere was the New England coast as noble, Yard wrote in National Parks Portfolio, a government-printed book sent to leaders for free to advertise the merits of the growing national park system.

The merging of ocean and mountain was not all that stirred those who wished to preserve the prime parts of Mount Desert Island. The island had become a desirable and exclusive vacation spot for American elites, and they wished for it to remain a rustic refuge from urban America.

When middle-class families began buying lots for cottages, the "gentlemen of means," as Runte described them, organized to stop them. They formed the Hancock County Trustees of Public Reservations, a nonprofit trust that purchased land and held it tax-free for recreation. This required working with the local water company who condemned the land, saying development would foul Bar Harbor's water supply. Local real estate developers tried to stop the condemnation, but the elites managed to persuade Maine's legislature to allow it.

George Dorr, whose family made a fortune trading with China, drove these efforts. Charles Eliot, Harvard's president, helped Dorr and made a critical connection with John D. Rockefeller, Jr. The scion of the vast Standard Oil fortune eventually spent many millions on conservation, but his first donation was a modest $17,500 for the trust on Mount Desert Island. The next year, he gave 2,700 acres, valued at a quarter-million dollars.

This was 1916, and with Rockefeller's support, the trust had gathered 5,000 acres and gifted it to the federal government. (For context, this amount of land was not quite one-quarter of one percent the size of Yellowstone.) Woodrow Wilson used the Antiquities Act to create the Sieur de Monts National Monument on July 8.

Advocates for its preservation barely bothered with the scientific or historic rationale the Antiquities Act required. Instead Sieur de Monts represented what historian Hal Rothman called a "consummate way-station monument." Everyone recognized the monument status was holding on until Congress converted it to a national park, something achieved two years later.

A challenge and paradox rested in the heart of Acadia—and not an uncommon one. Proponents had to beat back charges of elitism at a place whose existence was owed entirely to elitism. National parks have long sat in this tension—places open to anyone but also available mainly to those with time to travel.

Rockefeller compounded the elitist charges at Acadia by demanding to develop carriage roads through the park that sat well within the landscape but were too narrow for automobile traffic. The roads were so expensive, a local told the writer Terry Tempest Williams that Rockefeller "might as well have paved them with rubies." To Rockefeller's way of thinking, these carriage roads provided "a democracy of experience" (in Williams' words) for anyone, allowing even the elderly into the center of the park.

But for most of the American public a century ago—and now—the "democracy of experience" came from behind a car steering wheel. Dorr thought so but couldn't publicly complain about the carriage roads for, as Dorr put it, Rockefeller "does not welcome suggestions for which he does not ask."

Still, automobiles came to the park in the 1920s. Because Maine is comparatively close to population centers like Boston and New York, Acadia became popular. In 1919, 64,000 visitors came. Today, it remains one of the 10 most visited parks. Its elitism belies its popularity, as is true for many national park sites.

In The Hour of Land, Williams' critical engagement with the national parks on the National Park Service's centennial, she includes a loving meditation on Acadia. Although she is mostly associated with her beloved, confounding Utah, Williams has long-standing personal connections to Acadia (some ancestors are buried there) and calls it her "secret respite."

In her reflection, Williams drops one of my favorite phrases about the parks. After describing a hike up Champlain Mountain with her husband, Williams ponders: "Perhaps that is what parks are—breathing spaces for a society that increasingly holds its breath. Here on the edge of the continent in this marriage between wind and sea, the weaving of currents offers a tapestry of relief."

Breathing spaces. We—the non-elite and elite alike—need these places of pause where we can breathe easily. And wouldn't we all benefit from "a tapestry of relief?" Although I've not (yet) been to Acadia National Park, I share Williams's belief that parks like it offer something we desperately need.

Comments ()