Incongruous Claims

The persistence of mining in national park history

Mining the Parks?

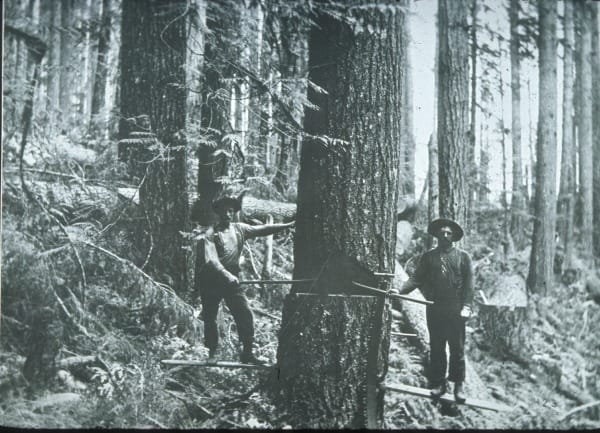

During the wilderness campaign I described in An Open Pit Visible from the Moon, conservationists rallied to protect Miners Ridge—an area threatened by Kennecott Copper Corporation's plans to develop an open-pit mine. Conservationists wanted to incorporate the area into the North Cascades National Park they were also advocating for.

Although Miners Ridge stood inside Glacier Peak Wilderness, nothing in the Wilderness Act prevented mining exploration or production. Mining in a national park would be harder, but not impossible

Mining claims and national parks remained unusually connected for a century before the Mining in National Parks Act of 1976 sort of disentangled them.

The 1872 Paradox

I have written before (also here) about the seemingly paradoxical convergence of the creation of Yellowstone National Park and the passage of the General Mining Act in 1872 a mere 10 weeks apart. One law established the first national park, carved out of the public domain and protected from exploitation. The other allowed prospectors to go virtually anywhere on public lands and claim land and mineral rights. The terms were easy and the costs small. These two laws seem at cross-purposes.

The mining law, still in effect and largely unchanged, facilitated thousands of claims across the country, privileging mining over virtually every other use. Its endurance has meant that some of those claims ended up within the boundaries of land later managed by the National Park Service—called inholdings.

This created an untenable juxtaposition.

From Mining Ad Man to Park Service Director

Before examining these mining claims in parks and monuments, it is important to look at another ironic connection between the Park Service and the mining industry.

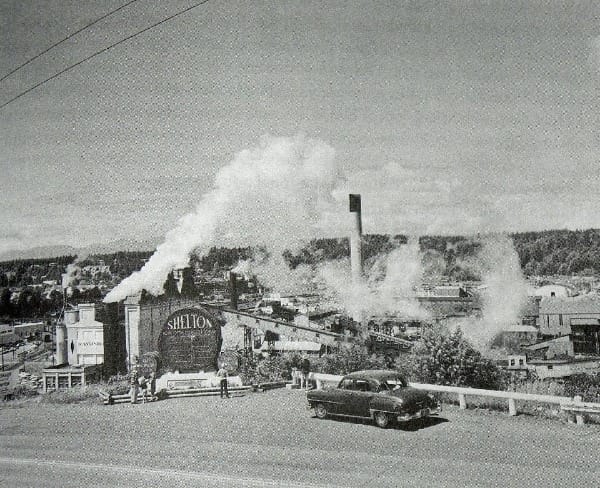

Stephen Mather, the agency's first director, began his working life as a journalist but quickly moved to industry, specifically the borax mining industry. Hired by his father to run the Pacific Coast Borax Company's advertising arm, Mather learned quickly how to sell products, quickly becoming a millionaire.

After visiting Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks in 1914, Mather wrote to Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane with criticisms about management. Lane responded, "If you don't like the way the national parks are being run, come on down to Washington and run them yourself." And he did.

Mining Death Valley

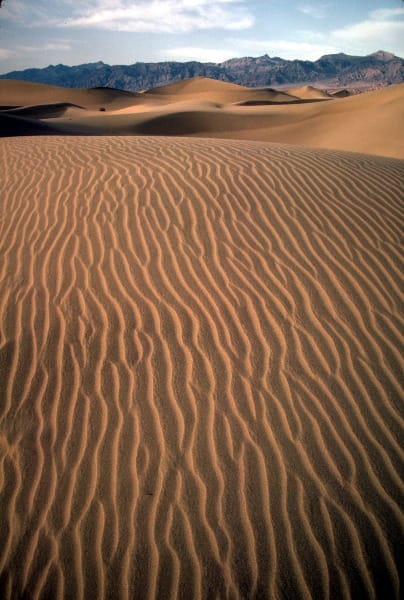

One place where the Pacific Coast Borax Company held mining claims was Death Valley. It had mined borax there, but by the mid-1920s, operations ended and the company opened a hotel. By this time, Mather had been in charge of the Park Service for a decade. He had not promoted Death Valley as potentially part of the park system for fear of being accused of being unethical. Besides, deserts were not yet appreciated widely in American conservation culture.

Soon, Mather left the agency in ill health, and the new director, Horace Albright, thought the "starkly beautiful piece of desert" belonged in the national park system. Albright had no conflict of interest to stop him. He persuaded President Herbert Hoover to create a national monument in Death Valley in the last weeks of his presidency in February 1933.

The proclamation contained a clause that protected "valid existing rights." Other national parks included similar language, which is why mining claims existed—and were occasionally worked—inside a handful of NPS borders.

Although the Pacific Coast Borax Company had found it unprofitable to continue mining, markets changed.

In 1971, Tenneco Oil Company started an open-pit mine inside the monument. Within two years, the company was mining 130,000 tons annually in a multi-million dollar business. From the NPS' perspective, the disposal of mining waste—tailings—was the worst aspect, because visitors could easily see it.

The situation became so untenable that two Arizona politicians from distinct wings of American politics—the liberal Representative Morris Udall and the conservative Senator Barry Goldwater—collaborated to pass a bill to stop mining in two Arizona national monuments.

Although that did not affect Death Valley, it showed how momentum was building for a solution.

Tenneco did not help its case, using bulldozers to carve roads and pits. The problem, as historians Hal Rothman and Char Miller put it in Death Valley National Park: A History (2013), was the "company's claims were valid and its methods legal, if not compatible with Death Valley's direction in the 1970s." The agency pushed for stricter compliance, but profits encouraged the company to expand its open-pit operations.

The superintendent at Death Valley, James Thompson, pointed out that even though the open pit was small relative to the size of the monument, it marred everything. He told a reporter it was "like a mole on your face. It's in one spot, but it affects everything."

A System-wide Solution

Media reports about mines in Death Valley and Denali and attention from environmentalists raised alarms about this mining in the national park system. Members of Congress braved the summer heat in July 1976 for a field visit to the California desert. By October, the Mining in the Parks Act went into effect.

This law closed parks to new claims, effectively limiting the 1872 General Mining Law, one of the few restrictions placed on it. It did not extinguish existing claims, but it gave the NPS more power to regulate.

In Death Valley, for instance, the NPS sued to stop a mining company from surface mining. That is, it forced a mining company to do the more expensive belowground mining, a prospect that made the enterprise unprofitable. This represented a victory to the conservationists who long recognized the incompatibility of mining inside national parks and monuments.

Never widespread, mining claims inside the national park system presented the problem of inholdings and the primacy of the 1872 General Mining Act. Wherever these existed, the potential existed for industrial activity and unsightly and incongruous images abutting the scenic wonderlands that parks symbolize. For decades, this potentiality seemed impossible to stop. But eventually, such incongruities faced limits.

Comments ()