Independence in the Woods?

A glimpse of logging in postwar Washington

Born in the brown sandhills of Idaho, Margaret Elley came to Washington where the green forests captivated her. “I would look up into the tall giants where the sun came shimmering through the thick green branches, caught in the spell of their beauty, and sigh,” she remembered.

Life and love, though, had other plans for her and her love of forests.

In 1934, when she was just 16, she met Sonny Felt. He waited three years to date her; three years later they married in 1940. And Sonny was a logger. “His viewpoint was strictly commercial and mine strictly aesthetic,” Margaret Elley Felt wrote in her memoir Gyppo Logger published in 1963. The clashing views of forests fed some arguments over the years, but they united in their business venture.

The Felts made their way into the Washington woods at a time when independent logging outfits could make a go of it. A convergence of trends allowed these small, often family-run operations to succeed as they never had before, although failure always lurked in the ups and downs of the timber economy and unstable relationships with larger companies.

Independent loggers existed from at least the 1910s. Unions hated them, seeing them as essentially scab labor. Timber companies often specifically hired these outfits to undermine union wages. The companies would contract with these independent operators to cut a certain block of forest or certain amount of board feet often with a limited amount of time—all factors that could lead to cutting corners. The small operation took all the risk; the company stood to gain most of the profit. By the 1940s, when the Felts were in the Cascades knocking down trees, some timber companies had subcontracted virtually all their cutting to gyppos. Labor organizing meanwhile shifted almost entirely out of the woods and into the mills.

It took a certain type of person to work happily in this system.

“You start off with an impulsive, stubborn, hard-working guy who’s got the logging virus in his veins,” Felt explained; “add a couple pieces of haywire equipment purchased on extended credit; introduce him to a ‘loggin’ show’—a stand of timber—and you’ve got your gyppo.”

By the 1940s, that “haywire equipment” probably was war surplus. The debt might be held by family or friends, but it could be a large financing firm in Seattle (at an exorbitant 12% interest in Felt’s experience) or a small rural bank. The company itself might extend credit, another way for it to hold leverage over the operation. At this time, logging railroads were shutting down and logging trucks were firing up.

Trucks, obviously, were far easier for a small outfit to own and operate than a railroad. This could be a route to sustained independence. Trucks also were yet another piece of equipment to be indebted for, a practice that continued for decades.

In his account of the timber wars in the 1980s, The Final Forest, journalist William Dietrich described a family in Forks, on the Olympic Peninsula, who bought a logging truck in 1979 for $75,300, or the equivalent of a medium-priced home. It represented independence, because the family could get paid by the load. But it was a precarious living. “We lost the farm and saved the truck,” the family patriarch told Dietrich. A decade later, the costs for upkeep, repair, fuel, and taxes ran $33,500 a year. Independence had its costs in this postwar era.

A final new technology that facilitated the expansion of independent loggers was the gas-powered chainsaw. They became widespread just after World War II, in time to be added to the gyppo’s toolbox.

Altogether these trends added a relatively easy way for an “impulsive, stubborn, hard-working guy” to envision a way to get ahead by heading to the forest for months at a time.

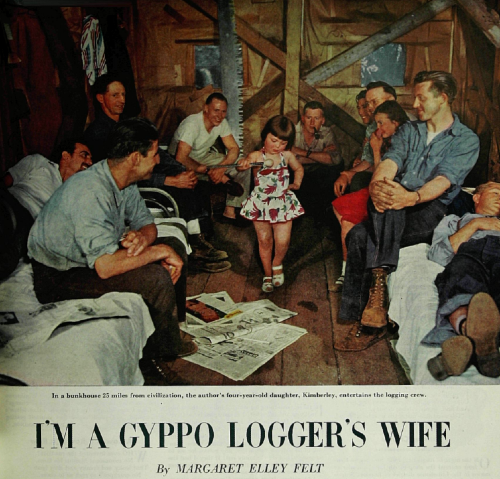

This way of life could also be a source of some independence for women. As Gyppo Logging makes clear, Margaret drove trucks or the cat (i.e., bulldozer) sometimes. She took care of most of the financial arrangements. At times she was the camp cook. These jobs—for wives anyway—were not paid but were essential to the family business.

In the book, it was stated, “a woman’s place is not necessarily in the home. It is wherever she wants to be.” The words, Felt insisted, were her husband’s. She pointed out that their lender took “several years . . . to actually accept me as Sonny’s full partner in our logging setup.” Sonny’s insistence that she share in “everything from the rough work to the financial responsibility” led the way to acceptance. This was no small feat given the context of the time.

Yet the independence either Sonny or Margaret experienced could change quickly. After seven years, the company they contracted with—always labeled simply the Big Company in the book—abruptly ended the relationship.

“We had always figured the gyppo logger had a definite place in the logging industry, but now the notion was creeping up on us that a gyppo logger’s little outfit was like a ripe plum on a tree, to be squeezed dry of its value and then cast aside, and another gyppo employed until he, too, went broke; and so on and on,” Felt mused, frustrated.

The sort of exploitation that is described here certainly pulls at one’s sympathy. The unions might have pointed out that solidarity could have helped withstand that. However, independence meant success or failure alone. On the other hand, the next season when looking for work, they had a job lined up when a three-month strike in the mills “loomed its ugly, time-wasting head” and shut down logging before they could get to work. Such were the vagaries of gyppo logging.

Felt may have become part of a gyppo operation, but it never completely displaced that older admiration of the forest. “Untouched timberland” fired her imagination even if she knew that “sooner or later man will begin his insidious operations—tree by tree, acre by acre, section by section—and the land will be robbed of its precious forest cover,” Felt lamented, adding her solution: “If they would only replace what they take with reforestation!”

Reforestation was her solution, along with selective logging. Reforesting after logging had been the law in Washington since 1946, but enforcement proved lax, at best. Still, Felt had faith in nature’s regenerative power and by the end “I finally came to realize that timber is a crop, and should be harvested just as any other crop, when it is ripe.” The conclusion she drew made sense in the world she came to live in—one of economic uncertainty amid apparent bounty. The worldview seemed a path to independence, although a forest’s path always is interdependent.

Comments ()