King Sequoia!

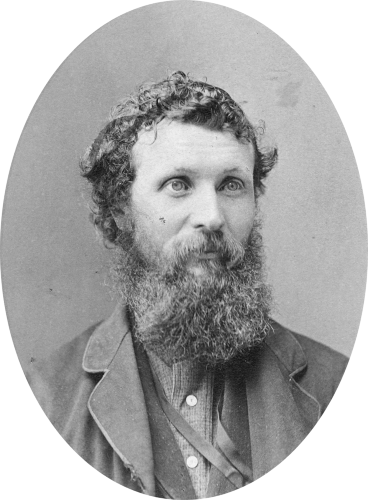

The 1875 journey that inspired John Muir

On the last day of July 1875, sitting in Black's Hotel in Yosemite Valley, John Muir took a moment to write a letter to his trusted friend and mentor Jeanne Carr.

Muir had just returned from climbing Mount Whitney and was deciding what to do the rest of the summer. His landlord thought Muir should return to work, but Muir really wanted "to go with the Sequoias a month or two into all their homes from north to south, learning what I can of their conditions and prospects, their age, stature, the area they occupy, etc."

He chose to ramble among the trees. The adventure became a turning point in his life.

Muir borrowed a mule and headed south from Yosemite Valley. For much of August, all of September, and nearly all of October, Muir and the mule followed the range of the sequoia, "Nature's forest masterpiece."

The single-person expedition carried a scientific cast. Muir measured and assessed. He sought elevation ranges and latitude limits. No one knew much about these trees and where they grew. The Europeans and Americans had found the sequoias in small groves only a quarter-century before as the Gold Rush pushed people into the foothills and mountains in search of riches.

Some found something of value in the big trees beyond money. Muir was one of them.

Muir never tired in his journal and subsequent writings of trying to capture the best way to convey Sequoia gigantea (now, Sequoiadendron giganteum). The auld lang syne of trees. Antediluvian monuments. Emblems of permanence. Ancient of other days. Venerable-looking. Serious-looking. The very god of the woods. King Sequoia.

King Sequoia! There is health and life in his very looks, in the air he breathes, in the birds he keeps, in the squirrels that gamboled in his arms, and the flowers that blow and the streams that flow at his feet.

He scrawled those words in his journal 150 years ago this month, barely containing his excitement, at the end of his months-long sojourn through the sequoia groves, covering some 600 miles according to historians' estimates.

Some of the sequoia groves Muir saw are still preserved in this area within Yosemite, Kings Canyon, and Sequoia National Parks. Photos distort them, their scale not readily captured. Light touches their tops while their roots remain resting at dawn. It is easy to imagine them as part of a giant's world

The prose that came from Muir out of this sequoia scouting trip stretched in two directions.

First, Muir wrote scientifically. The very month he returned to Yosemite Muir published an article in Harper's Monthly about glaciers in the Sierra. By 1877, his natural history observations about the sequoia forest appeared in the prestigious Proceedings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. A voracious reader at this time might have seen the Muir name more frequently and expected him to make his name in science, for he made discoveries in the Sierra Nevada that put him in the forefront of natural history.

However, Muir also grew alarmed through his sequoia season. Five sawmills bordered the various sequoia groves. One of them, Hyde's Mill, had cut two million board feet in 1875 alone. In February 1876, Muir wrote a long letter to the editors of the Sacramento Daily Union, describing the trees.

But waste and pure destruction are already taking place at a terrible rate, and unless protective measures be speedily invented and enforced, in a few years this noblest tree-species in the world will present only a few hacked and scarred remnants.

Muir pointed accusing fingers at fire and the ax, saving his greatest ire sheep herders who set fires to promote better pasturing which was a practice he believed was "very destructive to all kinds of young trees."

Later, he put it more descriptively:

The destruction, in great conflagrations, of fine buildings on which loving art has been lavished, sad as it is, seems less deplorable than the burning of these majestic living temples, the grandest of Gothic cathedrals.

Muir could walk through a forest and identify plants and birds and insects. He could climb mountains and see glacial influences. He could track the characteristics of trees and make intelligent guesses about their evolution. All of these would further a career in natural history and science.

But he loved nature in a different way, something that his 1875 sequoia trek reinforced and expanded. In effect, he committed to writing for a cause. And the cause was nature.

In 1890, 15 years after Muir's interlude in the sequoias, Congress created Sequoia National Park, the nation's second. That same year, it also added General Grant National Park, a small area (just two square miles) that protected the General Grant Tree that is now part of a much-larger Kings Canyon National Park, as well as Yosemite National Park, which included the Mariposa Grove of sequoias.

A decade later, Muir spun out articles about the proliferating national parks in the Atlantic Monthly and collected them in his 1901 book Our National Parks to highlight and promote the parks. The next-to-last chapter in the book is called "The Sequoia and General Grant National Parks," and it retells the story of Muir's discoveries in 1875, seasoned over the decades.

Last month, during the fading light in the evening, beneath the big trees, I read that article half a mile from General Grant Tree. This beats the basement study carrel where I read it the first time in 1994 as I studied Muir in the first major history project I undertook.

I discovered, as Muir had, that being in their presence makes a difference. He concluded, "In Nature's keeping they are safe, but through man's agency destruction is making rapid progress, while in the work of protection only a beginning has been made."

That small beginning has grown. Standing among the trees 150 years since Muir's journey, I could see what protection has preserved–and what work remains.

Comments ()