Leave It As It Is

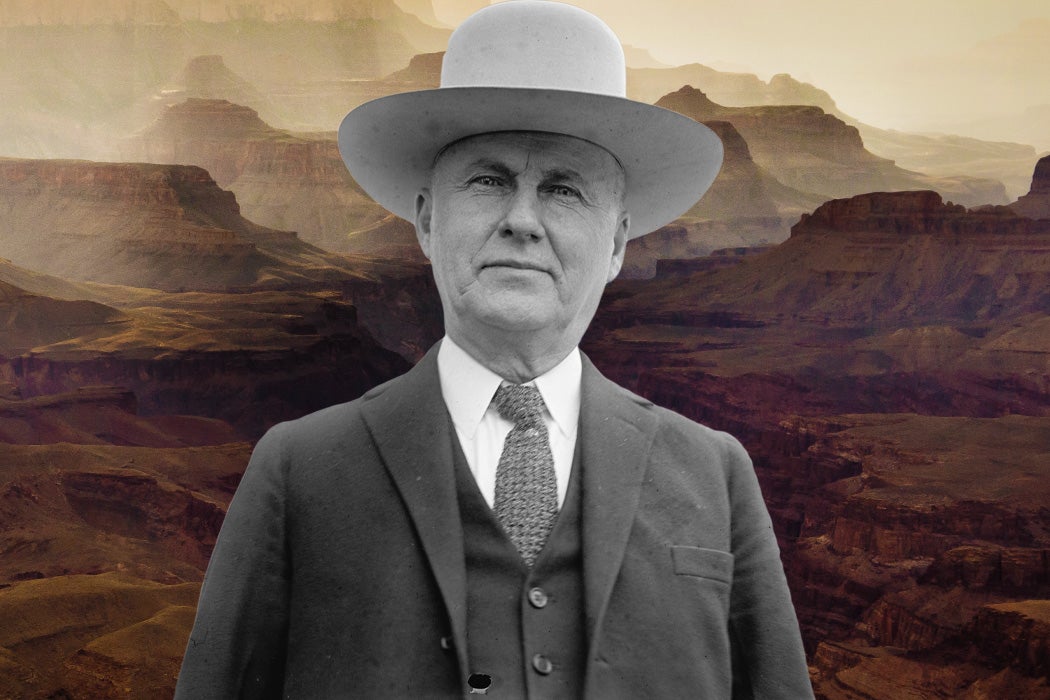

Theodore Roosevelt and the Grand Canyon

Before dawn one Wednesday morning in May 1903, residents of Flagstaff, Arizona, gathered in large numbers at the train station. A train passing through needed water, and those who stood in the dark hoped the president might have awoken early and would make an appearance from his personal car.

He didn't, disappointing the crowd. But by 6:00 AM, more than 300 of Flagstaffians hopped on another train and followed Theodore Roosevelt to the Grand Canyon. They were not disappointed there.

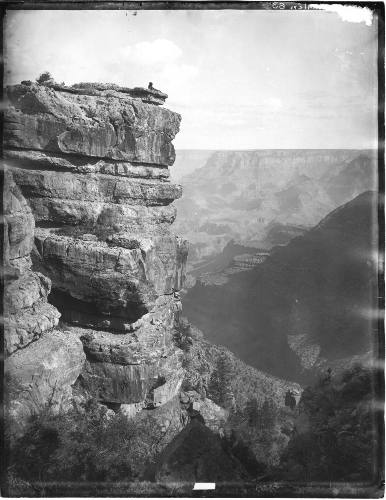

The gap between trains allowed President Roosevelt to go horseback riding and inspect the Grand Canyon. Although he had read reports of it, Roosevelt was seeing the canyon for the first time. It jarred something inside.

Anyone who has visited probably knows the feeling Roosevelt experienced. You are aware of the canyon's size, have read descriptions of it, maybe even have seen images of it, but nothing quite prepares you for being there.

It awed Roosevelt.

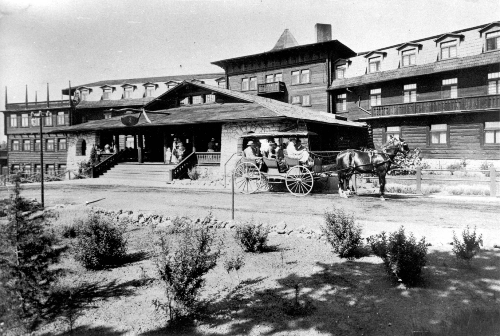

The president returned to the Grand Canyon train station just as the Flagstaff train arrived. At a reception at the Grand Canyon Hotel, Roosevelt gave a short speech to the 800 people who had gathered at the rim.

Roosevelt called out to some Rough Riders in the audience who had fought with him in Cuba a handful of years before.

Then, the president touted his administration's efforts in Arizona to develop irrigation (a partial subject of my Master's thesis), which he said would bring "permanent good results for the community." (These words don't appear in the official remarks linked above but appeared in the more extensive original reporting from the Coconino Sun.)

Finally, Roosevelt moved on to the Grand Canyon, a topic that inspired his eloquence, despite his claim that he would "not attempt to describe it, because I cannot. I could not choose words that would convey or that could convey to any outsider what that canyon is."

Roosevelt urged those in attendance, many of whom presumably were local and capitalized on the burgeoning tourist trade, to leave the canyon alone. The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad had decided not to build a hotel on the rim, a decision he praised.

The president wanted nothing "to mar the wonderful grandeur, the sublimity, the loneliness and beauty of the canyon."

Then, the crux:

Leave it as it is. Man cannot improve on it; not a bit.

The only thing the Arizonans should do, Roosevelt said, was keep it for "your children and your children's children." Doing so would be a great act of citizenship.

Roosevelt ended by addressing the Native peoples who attended. (These remarks [including a short exegesis on virtue not included in the official remarks] are probably worth an entire essay on their own, but they take us away from the Grand Canyon, which is the subject at hand.)

Some historians and writers have suggested that Roosevelt's morning ride inspired the soaring language he included when speaking from the balcony of the hotel. How could glimpsing this overwhelming place not affect his prepared remarks? It also planted a seed of dedication.

The sentiment that Roosevelt voiced—leave it as it is—burrowed inside of him and made him determined to act. (David Gessner's book Leave It As It Is tells this story well and raises its currency to the present.)

As far back as 1882, Senator Benjamin Harrison had introduced legislation to create a Grand Canyon National Park. After he became president, Harrison created the Grand Canyon Forest Reserve in 1893. But that designation did not prevent mining claims, which were being deployed to extract money from tourists more than minerals from the earth. The most notorious examples were by a local politician named Ralph Cameron (who I wrote about in the link below).

By the time Roosevelt visited in 1903, the Grand Canyon faced unsteady federal protection because forest reserves allowed all sorts of economic activities. More than anything, though, tourism threatened this canyon, which was why Roosevelt expressed gratitude for the railroad's restraint from building its hotel at the rim.

However, by 1905, the railroad had built the hotel after all, and it now stood at the canyon's edge, the famous El Tovar Hotel.

The following year, Roosevelt declared the canyon a game reserve to slow further development and prevent more mining claims from dotting the canyon.

That wasn't enough.

Fortunately, the same year he created the game reserve Congress gave Roosevelt—and all presidents—a powerful tool: the Antiquities Act. This law, which I've written about here before (and elsewhere, too), gave presidents the power to reserve federal lands where "historical landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest are situated" as national monuments. The legislation required that these reservations would be "confined to the smallest area compatible with the proper care and management of the objects to be protected." Yet, the law also left this up to the president's "discretion."

Roosevelt wasted little time using the Antiquities Act. The law passed in June; by September, he had created Devils Tower National Monument.

Meanwhile, tourists continued to flock to the Grand Canyon and Cameron had hatched a plan to run an electric railway along the rim. Roosevelt had had enough.

If Congress was drowsy, Roosevelt was going to wake it up; if it was operating in the gutter, he was going to teach it to look at the stars. His job as president was to procure the most happiness for the most people.

That's how Douglas Brinkley put it in his biography of Roosevelt, The Wilderness Warrior, capturing the expansive vision the president had for his role.

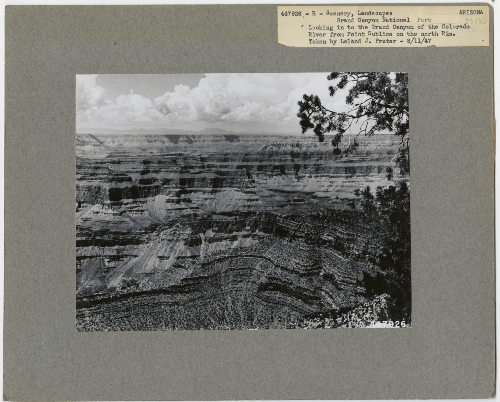

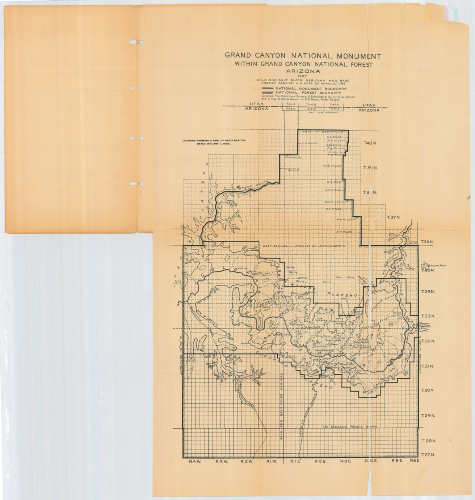

Congress had not acted since legislation was first introduced in 1882, so Roosevelt grabbed the power embedded in the Antiquities Act and proclaimed more than 800,000 acres for a Grand Canyon National Monument in 1908.

Historians have interpreted this to Roosevelt's boldness and his nationalism. The Grand Canyon, Roosevelt said that day in 1903 from its edge, was "one of the great sights which every American, if he can travel at all, should see." It was a place worthy of the great nation.

Eleven years later, Congress upgraded both the Grand Canyon and Acadia to national parks on the same day.

The story of Roosevelt and the Grand Canyon emphasizes that power of firsthand experiences to sharpen commitments. It also reveals the common history around public lands, including threats not only from extraction but also from tourism and the frequently shifting federal designations that reflect distinct purposes and different urgencies. All of this is a reminder that these places have long been sites of conflict worth fighting for to protect their material and symbolic values.

Sad Postscript

Comments ()