Legalizing the Illegal

How American expansion was built by lawbreakers

A common refrain you can hear from Americans who oppose illegal immigration is that are not anti-immigrant but simply want immigrants to come legally. Many who express this idea are quick to claim that their ancestors came to this country legally. This is possible.

But many white Americans violated laws in their westering ventures. And Congress found ways to reward or forgive these lawbreakers, time and again. Rather than calling them “illegals,” history typically calls them “pioneers.”

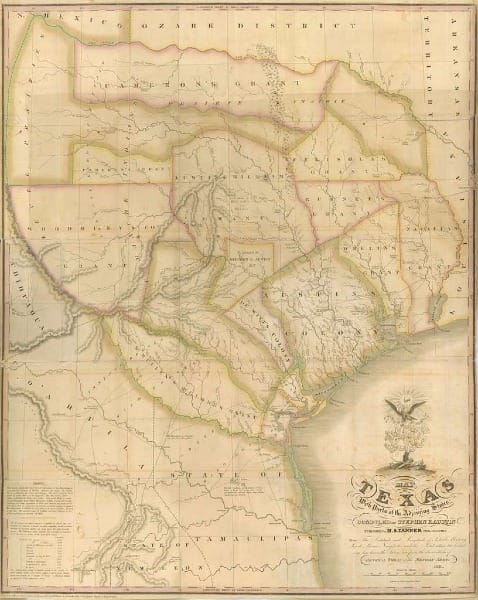

The Illegal Founding of Texas

As if proof that irony is dead, Texas furnishes one of the best examples of this dynamic.

Mexican independence dated to 1821, but its northern borderland remained sparsely occupied by Tejanos.

American filibusters–not much better than mercenaries–disrupted this region, potentially wreaking long-lasting havoc. But the Mexican government believed (or hoped) that these Americans might provide a bulwark against tribes like the powerful Comanche empire then at the height of its power. The Mexican government also thought Americans could assimilate and become loyal Mexicans.

So the Mexican government agreed to a contract with Moses Austin in 1821, granting him huge tracts of land while he would import 300 Catholic families to establish communities in northern Mexico.

Despite this orderly plan, by 1823, about 3,000 illegal immigrants occupied northern Mexico. In response, Mexico passed the Colonization Law of 1824 to extend a generous policy, complete with tax breaks and free land, that more or less legalized what was already happening.

Mexico was operating much like the United States: attracting immigrants, expecting assimilation, and believing settlement would displace Indigenous peoples from their homelands.

Mexico’s plan might have worked. Stephen Austin carried out the colonization plan of his father and entered into more contracts to bring nearly 1,000 new families to Texas. Austin had become a loyal Mexican, an officer in the army even. By 1830, 7,000 Americans lived in Texas, more than double the number of Mexicans.

The trends bothered some in the Mexican government, for good reason. In 1829, Mexico had outlawed slavery, but Americans didn’t care. The following year, Mexico ended its colonization policy and specifically banned further American immigration, a ban that lasted only a few years. None of this worked to stem the tide of illegal immigration. By 1835, 30,000 white Americans had arrived along with 3,000 enslaved people.

For these (and many other) reasons, war broke out, Texas became an independent republic, and later joined the United States shortly after which the United States and Mexico fought another war. The wars are not the point here. The point is Americans invaded a sovereign territory in open defiance of that country’s laws and expected to be allowed to continue without problems.

Squatting into Legality

Although quite dramatic, Texas wasn’t the only place where illegality paved the way for American settlement.

I have written before in Taking Bearings and in greater detail in Making America’s Public Lands some of these details.

From the beginning of the republic (and even a little before), the nation declared its intention to systematically survey and sell the public domain once it obtained title (something mostly overlooked). However, surveying took time, and farmers were impatient. They moved onto land before the law allowed and squatted–that is, they started the work of clearing the land, building homes and barns, and farming without any legal right.

As I wrote in Making America’s Public Lands:

Squatters seem quintessentially American. They were the go-getters, the pioneers, those who became the stuff of ballads and folktales.

But it is important to note that, this celebration was not foreordained. Squatters caused huge national headaches. Their presence generated conflict and started wars with Native nations that required federal intervention and expenditures at a time when the nation was weak and poor. Congress passed a law in 1807 explicitly calling such people trespassers. And yet . . .

As more people moved and as territories west of the Appalachian Mountains became states, attitudes softened. Soon, the House Public Lands Committee stopped castigating them and started encouraging them. Accommodating lawbreaking became part of land law, effectively redefining illegal migration (and immigration when it went beyond national borders before wars of conquest caught up) into civic virtue.

A US Representative from Tennessee, Balie Peyton, characterized these squatters in Congress:

He had chosen that spot as the home of his children. He had toiled in hope. He had given it value, and he loved the spot. It was his all.

That lawbreaker, Peyton said, should have the right to that land. This evolution in perspective required legal redefinitions.

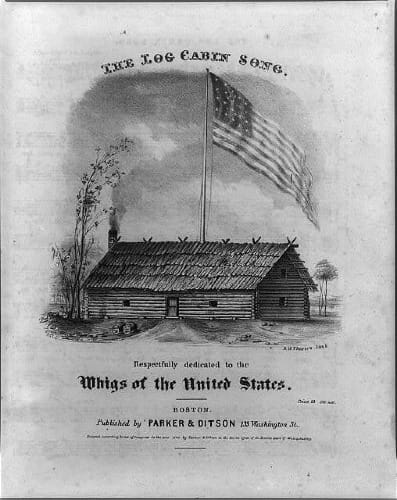

Congress passed several laws to accommodate, if not outright encourage, squatting, although it used the kinder term “pre-emption.” The most important pre-emption law passed in 1841 and was commonly known as the Log Cabin Bill. Such laws gave squatters the right to buy the land they illegally occupied.

What had once been a process led by riffraff that produced problems had transformed into what one leading scholar characterized as “an honorable step in the pioneering process of farm ownership.”

Looked at critically from one angle though, it celebrated lawlessness and called it national interest.

Rule of Law?

Last Saturday, walking through the crowds at a local #NoKings protest, I noticed a sign reading something like, “There can be no illegal immigrants on stolen land.” Such a clever slogan forces some rethinking about American history.

It doesn’t take long, if you know enough history, to realize that a whole lot of illegality built this nation until a war or a law of Congress declared that such laws don’t really matter. Lawlessness, unfortunately, is an old American tradition.

In Other Words

Last weekend I shared my latest profile that is available for paying subscribers. It’s an especially good one, I think. Become a paying subscriber to read about brilliant historian Flannery Burke.

Comments ()