Making the Vastness Visible

McKenzie Long finds deep stories of the land

Introduction

I like to connect to people with similar interests, but my networks are cramped and my introversion can be a hindrance. So I am always grateful when someone else can provide a useful introduction. A friend and colleague (and previous subject of a Taking Bearings interview), Char Miller, introduced me to McKenzie Long by email. He sensed—correctly—that we shared many interests and aims in our work. McKenzie also focuses on public lands, but her 2022 book on national monuments somehow escaped my notice—something I quickly corrected which has now benefited me significantly.

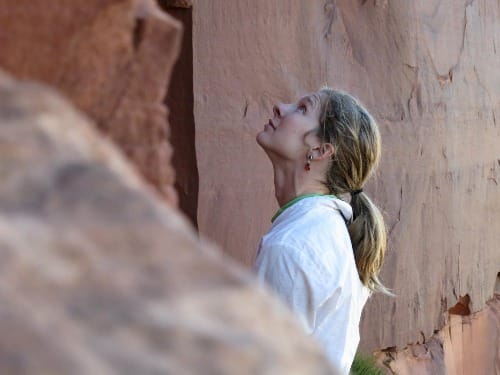

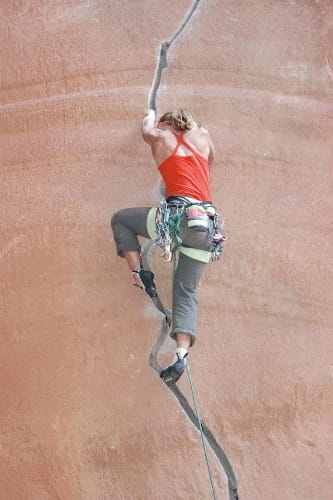

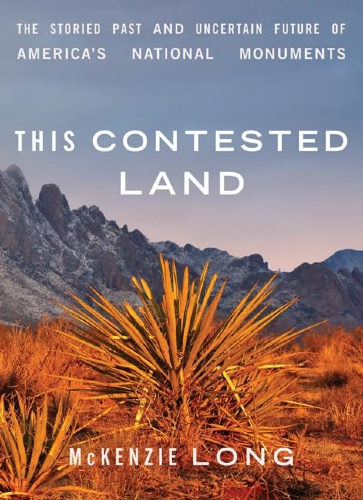

A writer and graphic designer, McKenzie lives in the eastern Sierra Nevada, among spectacular public lands that inspires her work. She has coauthored two climbing books, combining her love of writing and rock climbing. She has earned two residencies at Hypatia-in-the-Woods and was named a 2019 Terry Tempest Williams Fellow for Land and Justice at Mesa Refuge. In addition, she benefited from the unique AWP Writer to Writer mentorship program, working with Kathryn Aalto. (This year, McKenzie is a mentor herself.) All these honors and support helped her while she completed This Contested Land: The Storied Past and Uncertain Future of America's National Monuments (University of Minnesota Press, 2022), a book that earned a Foreword INDIES Gold for Ecology and the Environment.

McKenzie is hard at work on her next book, which again will dive deep in public lands. Her latest endeavor, a monthly newsletter called This Land, touches on themes that will appear in that book, themes that will be familiar to any casual reader of Taking Bearings.

Growing through the Outdoors

Everyone who finds their way to public lands writing tells a different story. But none that I have heard before started in Cincinnati and included graphic design. Fortunately, good stories come in many forms, and unexpected turns make for greater interest. Perhaps because of the comparatively circuitous path, I found McKenzie Long's book, This Contested Land: The Storied Past and Uncertain Future of America's National Monuments (2022) to be especially useful—not only informative, but insightful; not only factual, but personal; not only sharp, but graceful in its prose.

Growing up in Cincinnati, Ohio, McKenzie had an early affinity for the outdoors through family camping trips and a desire to work with words.

I always wanted to be a writer, like many kids. When it came time to choose a college focus, I was in the position where I had to pay for school myself, and I worried that if I majored in creative writing or English that I wouldn't be able to find a job afterwards. So I chose graphic design, which was another interest of mine. And I do love it. I have been able to build a freelance career that fits into my lifestyle and keeps me engaged because it requires creativity and thought. There are a lot of similarities between writing and design: the goal of both is clear and elegant communication.

At the University of Cincinnati, design students alternated three months of coursework with three months of work. One of her co-ops was with the National Park Service Interpretive Design Center in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. There, a coworker extended an invitation that altered McKenzie's trajectory.

She came up to me one day and said "Hey, I go rock climbing at the gym every Tuesday. Do you want to come?" I didn't know anyone there, so I was like, "Yeah, I do." I started climbing with her every week. Later she brought me on my first outdoor multi-pitch climb at Seneca Rocks in West Virginia, which is a ridge of tall fins of rock. When you climb them, you end up on these tiny pointy summits and a big valley drops away beneath you. On the top I was thrilled by the exposure. She said, "I thought you would either freak out or love it up here. I'm glad you are loving it."

McKenzie was hooked: "All I really wanted to do was rock climb for a good decade.” Well, not all; she also found time to become a cross-country Mountain Bike National Champion.

The Circuitous Pull of the West

While McKenzie was finishing college and honing her outdoor identity, her family moved to Texas while she stayed in Cincinnati. This felt like a loss—"I grew up in the Midwest, and I still identify as a Midwesterner."—but there was some freedom to explore, too.

McKenzie was hired for an internship with Alpinist, a magazine based in Jackson, Wyoming, a place significantly different from Cincinnati. Without her family still in her hometown, the choice to move west was easy.

Growing up in Ohio, I never knew that there was such a thing as a mountain town or mountain town culture. I got there and I thought, "This is the life I'm supposed to lead."

After two and a half years, life intervened—a lost job, a breakup, the end of a lease—and pushed her toward another mountain town, Mammoth Lakes, California. She met someone on a climbing trip who told her:

“You know, there's way better rock climbing in California than there is in Wyoming. Why don't you try coming here?" And I realized, "What have I got to lose? I'll just go and try it. I could come back to Jackson if I hate it." So I came to Mammoth, and he was right. There's a lot more rock climbing here, a lot more big mountains. I love it here. I've been here for 16 years now.

Writing crept back into McKenzie's professional life in Mammoth, too, initially through writing gear reviews for a company called OutdoorGearLab. While the writing was not especially creative, it kept her hand in the craft. She eventually left that position and longed to do more. She took some online classes and began searching for a subject that resonated more deeply than equipment specs. She found it in Bears Ears National Monument.

I knew I wanted to write about that place because I had climbed there a lot and had come to care about it. And so I started doing a little bit of research. The more I learned, especially about history and current events, too, it just kept getting more and more interesting.

There are all these different layers to peel back, and I realized it was an interesting creative challenge to write about. All of a sudden I felt like the place had a lot more meaning once I learned all of these different things.

Embracing Complexity and Layered History

This realization—that intellectual engagement with a place’s history deepens the physical experience of it—has become a hallmark of McKenzie's work and is why This Contested Land will be enjoyed by so many Taking Bearings readers. She describes a shift from simply enjoying the landscape to understanding the often difficult narratives embedded within it.

This was a theme in my book, being able to hold both of those things—the tragedies and the wonderful—at the same time. There's something more intriguing about that than there is to ignoring the bad, it gives a place richness. It's more interesting, like when you eat something that has a very deep flavor. Something that's flat or one-dimensional is boring, flavorless. Something with layers tends to stick in your heart and mind and becomes more precious.

This perspective shapes how she views political conflicts over public lands. Rather than being simply adversarial, McKenzie seeks the nuance. She notes that even those who oppose national monuments often display a deep care for the same places.

It's easy for the environmental movement to villainize people that are anti-monument or anti-public land. And I don't think that that's an accurate portrayal. At least not all the time, because people can be opposed to government regulations and still care deeply about a place.

It forces a complex balance. "Nothing is ever just one thing,” she says, a lesson hard to apply in the too often black-and-white rhetorical world of the 21st century.

The Elements of Non-Fiction

McKenzie expertly deploys three elements in her book: personal experience, interviews with people involved with specific landscapes, and research. It's a winning combination and one she's not likely to change.

I guess I could write about something and leave my personal experience out of it, but I don't know that it would be very good. Sometimes I feel like that's where my best writing is. I couldn't do it without research. I could easily write about my own experience going somewhere, but without talking to other people who really know that place, it would be one-dimensional, not as exciting.

This way of triangulating makes for good reading. It also helps ensure McKenzie explores perspectives she might not have uncovered otherwise. She describes something many writers discover doing this work.

After preliminary research, I would think there was going to be a certain story and then I'd go there and the story would be different. With Rio Grande del Norte National Monument in New Mexico, I really thought that place was going to be about water rights. Then I got there and started talking to people and that wasn't the story that emerged from being there at all. So I decided to pivot and tell the story that I actually had to share.

Her adaptability helps make the work resonate with immediacy.

Making the Invisible Visible

McKenzie views her work as a tool for visibility. This Contested Land focused on national monuments, a designation she found was often misunderstood by the general public.

People don't care about protecting what's invisible to them. And so I want to make places more visible and allow people to care more. With national monuments, many people I talked to did not even know what a national monument was, even though there's many them and they're often in the news. By writing my book, I was trying to show what these misunderstood places were like, why they're important, why they're worth caring about.

This mission continues in her current project, a book focused on the precarious state of public lands in the face of political and environmental crises.

For this next book, I want to look at different ways we're losing public land, and how we can still save it. The second Trump administration is removing public land protections and sneakily changing laws and regulations to erode public land in numerous ways. But I don't want it to be all about what this administration is doing. So I'm also looking at more evergreen topics like the problems of wildfires in the west, climate change, and different environmental problems that land also faces.

One element in McKenzie's writing and analysis that shines through is her light touch when it comes to a potentially explosive topic.

The only thing I can do is offer my perspective and do the best I can to present facts and truth. I hope that resonates with people. I don't want to take the approach of knowing more than anyone. Instead, the attitude I take as a narrator is, "Here is what I'm learning." I'm not trying to tell people what to think, just give them things to think about.

It's an approach more writers could benefit from adhering to.

She acknowledges the ambition of her newest project, while also admitting to moments of doubt that plague many writers. But with This Contested Land under her belt, she has shown she is up to the task.

Writing as Empowerment

Ultimately, McKenzie sees writing in an empowering way. She embraces the fact that no one needs formal institutional permission to be a writer.

I didn't go to school for writing. I've met people who feel like they can't take on a big creative writing project unless they have an MFA. It was really empowering for me when I realized, Oh, I can just do this. I don't have to go to school for this. Learning the craft is certainly important, but a formal writing education is not required. And that's freeing because then you can just go start doing it if you love it.

Despite the shadow of AI and decline in people reading, McKenzie remains optimistic about the human need for good storytelling.

People do care about real stories from real people. It's important to be sharing stories from a very human perspective, which creates empathy and makes the world a better place. I mean, part of the problem in our country right now is that there's this lack of communication between different groups. And so, we can attempt to communicate or share stories in a good faith effort.

And at times, all of this comes together, in a wonderful synthesis of history and land and story—a place where McKenzie finds joy.

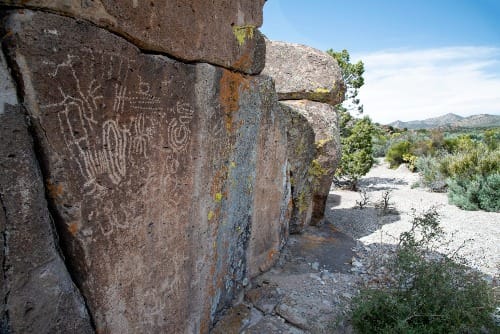

The most exciting part for me is when things come together and I start making connections. In my chapter about Basin and Range National Monument, I was learning about land artwork by Michael Heizer and then petroglyphs in the desert and then I heard about the project for a communication marker for a nuclear waste storage site and I felt like there were all these disparate things that were related in some way. In this case, it was ways of communicating through art. And they were all connected to this monument. I was like, "Wow, this is so exciting." That's partly history too, when you're finding little pieces of things and they all come together and connect. It's a really fun, amazing process and that's part of what I love about writing.

Me, too.

You can keep track of McKenzie's work at her website or her own newsletter, This Land. And you can support local bookstores when you order This Contested Land from here. You can also find her on Instagram and Facebook.

Comments ()