Pledging Allegiance

Historical (and other) notes on flag culture

The neighbors’ car-dealership-sized American flag scares my dog. On winter mornings or evenings when I take him out, the loud snapping when the wind is up makes him turn nervously in the dark to see what’s coming to get him.

Sometimes when I see the flag, I’m just as nervous.

Flag culture has changed in my lifetime. Decades ago, the American flag flew at schools and a few other places. We all knew what it symbolized, and we experienced it collectively. Now, it’s everywhere.

These days, it is sometimes hard to know what the flag symbolizes for the person flying it, as it, like so many other things, has become personalized. And I can’t keep track of what the flags with altered colors mean, but I’m suspicious. That goes double when the flag is the size of a house.

We are in the middle of a patriotic stretch of weeks–Memorial Day two weeks ago, Flag Day on Saturday, Fourth of July just around the corner. So I’ve been thinking about the flags and their rather varied historical function for patriotic piety.

Origins

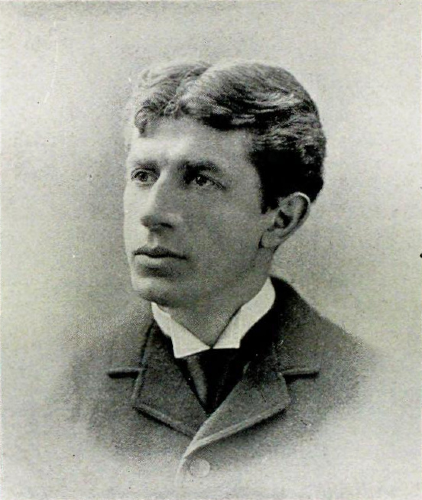

The Second Continental Congress adopted the flag on June 14, 1777. More than a century later in 1885, a schoolteacher in Waubeka, Wisconsin, organized the first observance of Flag Day. The son of immigrants, Bernard J. Cigrand, promoted Flag Day for decades before President Woodrow Wilson officially declared the holiday in 1916 with Congress following suit in 1949.

Growing up, we seemed to get out of school around Flag Day, which is, frankly, about the only time the holiday registered. However, the flag salute, or Pledge of Allegiance, was a daily ritual. Like many kids, I stood up and learned to recite words by rote far before I knew what a pledge or allegiance or a republic might represent.

The history of the pledge fascinates me from its founder, its legal squabbles, and its changes.

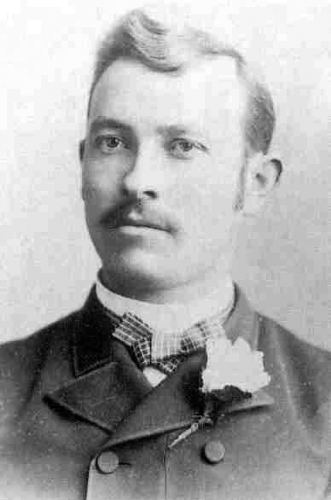

Francis Bellamy wrote the original pledge–“I pledge allegiance to my Flag and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all”–in 1892.

On the surface, the pledge served something of a performative and coercive purpose, a way of getting schoolchildren to inculcate patriotic expression without much critical thinking. In addition, one of Bellamy’s employers sold American flags to schools, so a flag salute ritual in the classroom promoted sales. This entire foundation could be seen as unseemly.

On the other hand, Bellamy was a onetime minister and Christian Socialist (and cousin to the utopian socialist writer Edward Bellamy whose Looking Backward, 2000 to 1887 imagined a grand socialist future). Bellamy had been driven out of one church for criticizing capitalism and left another church because it endorsed segregation. Bellamy emphasized indivisibility in the aftermath of the Civil War and believed the ideals of the nation while criticizing when they were not met in the harsh Gilded Age.

I’ve often wondered at what ostentatious flag-wavers today would do if they knew the author of the original Pledge of Allegiance had a goal of awakening “members of Christian Churches to the fact that the teachings of Jesus Christ lead directly to some specific form or forms of Socialism.”

The Pledge Goes to Court

The pledge’s text changed a bit in the 1920s and was made official by Congress in 1945, a few months after the end of World War II. During the war years, however, the flag salute in schools headed to the Supreme Court.

To inculcate patriotism, many school districts made a daily recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance mandatory and included punishments for refusing. This sort of enforced assimilation was a common function for public schools in the early 20th century as the nation incorporated millions of immigrants.

In a small community in central Pennsylvania, a place I spent a couple months studying, two Jehovah’s Witness students refused to participate in the compulsory flag salute because of religious beliefs. They were expelled. An 8-1 Supreme Court upheld the expulsions in Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940), stating that “national cohesion” was an overriding concern, despite a blistering dissent from Justice Harlan Stone who anticipated a bad aftermath.

Almost immediately, vigilantes across the country began enforcing flag worship violently, harassing other Witnesses and others who refused to participate. It took only two years for some justices to change their minds in Jones v. Opelika (1942) where three of them–Hugo Black, William O. Douglas, and Frank Murphy–in dissent acknowledged that they had been wrong in Gobitis.

The following year, the Court revisited the issue in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943) and overturned its Gobitis decision. Justice Black wrote,

Love of country must spring from willing hearts and free minds, inspired by a fair administration of wise laws enacted by the people’s elected representatives within the bounds of express constitutional prohibitions.

Symbolically, the Court announced its reversal on Flag Day, which should be a clear sign that the Supreme Court has long been a political arm of the government aware of its role as something besides a simple arbiter of legal truth.

God Arrives

There is one last Pledge/Flag Day coincidence to mention.

Religion became more prominent part of public life after World War II, something well described in historian Kevin Kruse’s One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America (2016). Primarily for partisan purposes (i.e., to criticize the New Deal), proponents of religiosity inserted God in the public sphere to a great degree. As the Cold War combusted, Americans enlisted religion in its ideological fight with the Soviet Union.

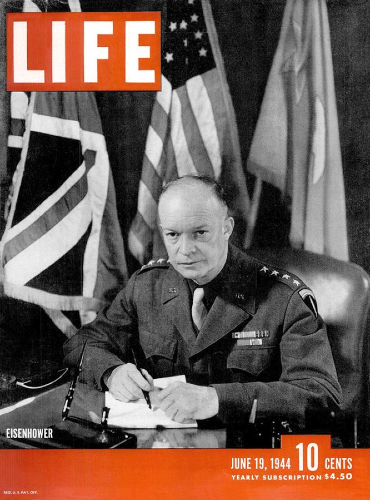

This converged in the early 1950s with a wide range of people who advocated for a more prominent place for God in the nation’s daily life. By 1956, “In God We Trust” had become the official motto for the United States and by then had been put on currency, coins, and stamps. But two years before, a similar campaign had culminated with a quiet presidential signature on Flag Day.

On the June holiday in 1954, President Dwight Eisenhower signed a law that inserted “under God” into the Pledge of Allegiance. He declined to make a public spectacle out of this, but others did.

Walter Cronkite covered an event related to this addition to the pledge, noting to his audience that

if we all remember to display our flags today and every special day, we will remember more clearly the traditions of freedom on which our country is founded.

From Communal to Individual Expression

Cronkite’s comment confirmed something for me. Americans mostly did not fly their flags all the time then, but maybe only on "special" days. Although 1954 was long before my time, I think that habit must have held into my childhood. It was only in adulthood when flag culture came to neighborhoods and trucks on every day that ends in -y.

John Prine's protest song, "Your Flag Decal Won't Get You Into Heaven Anymore," (complete with the song's backstory in this version) shows the flag has long been used for patriotism and protest.

Obviously there is no “pure” expression of flag-based patriotism (or protest). Traditions evolve; that’s their function. That Flag Day started with a son of immigrants is fitting and unsurprising. That a Christian Socialist wrote the first Pledge of Allegiance (and excluded mention of God) says something about the range of people who have given their allegiance to American ideals.

My dog and I are getting used to being snapped at by the neighbors’ flag, but neither of us likes it much. A flag-raising at school or a baseball stadium occurred with a gathering of the public. A flag on my house or your truck can express something more individualized. I worry how short a step that is to expressing a patriotism that is as individualized as a vanity plate and can be used exclude others.

Comments ()