Preserving Sanctuaries

Stegner, parks, and politics

Amid a critical campaign to keep a dam out of a national monument in the 1950s, American writer and historian Wallace Stegner wrote an essay — “The Marks of Human Passage” — to introduce a book he edited — This Is Dinosaur: Echo Park Country and Its Magic Rivers (1955). The book was part of a national effort to raise awareness about the threat to the national park system. The dam would flood part of Dinosaur National Monument on the border of Utah and Colorado.

The successful campaign represented the beginning of a national campaign for wilderness. After defeating the dam proposal, wilderness advocates mobilized the networks they built in favor of the Wilderness Act that they drafted — and then passed in 1964.

This history of this wilderness activism has been told well by historian (and my friend) Mark Harvey in two books, A Symbol of Wilderness: Echo Park and the American Conservation Movement (1994). Harvey set a precedent for seeing the Echo Park as a symbolic campaign.

A single passage from Stegner's essay perhaps serves as a lasting symbolic sentiment about national parks writ large and reminds us of the importance of sanctuaries.

The Importance of Saving Dinosaur

Dinosaur National Monument — originally just 80 acres — was set aside in 1915 by Woodrow Wilson for the eponymous dinosaur quarry. Franklin D. Roosevelt added the river canyons of the Yampa and Green in 1938, as part of what Stegner characterized as the “national rescue operation” of the New Deal that helped protect rangelands and farm fields and eroded watersheds.

Stegner didn’t just connect Dinosaur to the New Deal; he pegged it to his immediate time and future needs:

The consciousness of national guilt and mismanagement, and the press of necessity, were strong then; they are less strong now, when partially successful rescue work and a rainier cycle have temporarily healed some of the scars of the thirties. To this moment, at least, the Green and Yampa canyons have been saved intact, a wilderness that is the property of all Americans, a 325-square-mile preserve that is part schoolroom and part playground and part — the best part — sanctuary from a world paved with concrete, jet-propelled, smog-blanketed, sterilized, over-insured, aseptic; a world mass-produced with interchangeable parts, and with every natural beautiful thing endangered by the raw engineering power of the twentieth century.

Packed into those two sentences is a lot of history and politics and opinion. I came across it last week and have been mulling it over ever since.

It’s the middle section that struck a chord.

Parks' Purposes

I always appreciate the reminder that the public land system in the United States is the public’s land. (I have it on good authority that I was quoted on this point — made in Making America’s Public Lands — at a Hands Off rally in the town where I used to work.) I think considering public lands “property” belittles the full range of values such places embody, but Stegner’s cue that these are places for us all is important.

But what jumps off the page even more for me is the breakdown of the park’s purposes: part schoolroom, part playground, part sanctuary.

My initial reaction was that these nicely summarize the parks. They are places to learn — both the general public about natural and human history and scientists who investigate the life and physical sciences in relatively undeveloped places. They are places to recreate and experience the kind of sheer joy that only comes from hiking or canoeing or swimming in sublime outdoor spaces. They are places to know the sacred.

I expect this is mainly what Stegner had in mind when he wrote those words, because as he continued, he emphasized how these lands provided a needed respite from the made world.

These basic ideas are captured in the original mission of the National Park Service: “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and wildlife therein, and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

But something else is in there, too.

The Politics of Schools and Sanctuaries

After all, in the 1950s, the schoolroom and the sanctuary were political places.

The year before This Is Dinosaur was published the Supreme Court decided that segregated classrooms were inherently unequal. At the same time, American church-goers registered their highest participation rate in history.

These two facts pointed in different political directions, for integrating schools pushed toward social equality and American churches began organizing toward politically conservative causes.

Stegner was thinking more broadly about “sanctuary” than an actual church sanctuary, of course. The sanctuary he wrote about was a safe place, a protected spot, a refuge. A house of worship could be all those things. A classroom could be all those things.

But at least partly, we have chosen different paths, routes toward greater politicization. That is not as new as we sometimes think.

The same day in 1954 that the Court announced its decision in Brown v. Board of Education, a Senate subcommittee considered a constitutional amendment, a story related in Kevin Kruse’s One Nation Under God: How Corporate American Invented Christian America (2015). The proposed amendment read:

This Nation devoutly recognizes the authority and law of Jesus Christ, Saviour and Ruler of nations through whom are bestowed the blessings of Almighty God.

This hardly represented a sign of a healthy pluralism and tolerance.

Schools and religious sanctuaries have continued to be political since the mid-1950s. To some degree, this is inevitable, but the scale of it has eroded civic responsibility and notions of the common good, which have sometimes prevailed.

Maintaining Sanctuaries

I am not calling naively for the national parks or public lands to be places without politics. Such a desire is unrealistic and ignores the long history of competing interests in such places.

But for places like Dinosaur to remain sanctuaries, they have to continue to exist. Today, in the face of an extraordinarily radical assault on the nation’s founding principles and governing bodies, such a continuation is not assured. We must advocate.

Stegner ends the essay noting that, “In the decades to come, it will not be only the buffalo and trumpeter swan who need sanctuaries. Our own species is going to need them too. It needs them now.”

He was right – and it is up to us.

In Other Words

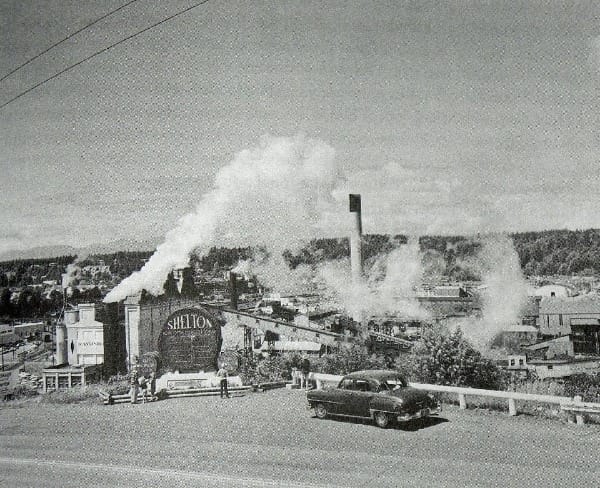

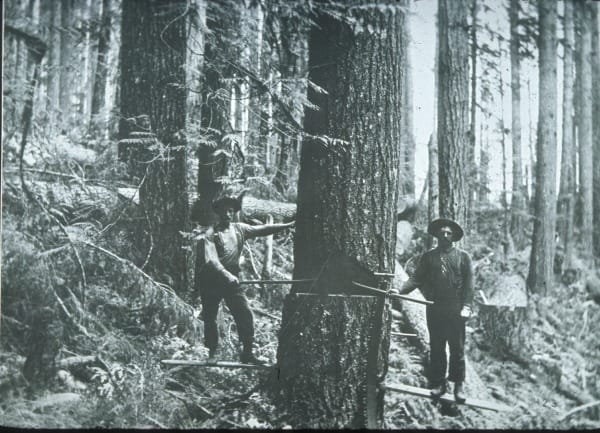

- At HistoryLink.org, I have a new article about experimental forestry in Washington. Have a look:

- In the local weekly, I wrote a story about the changing uses of a plot of land near downtown La Conner. Check it out:

- Angered by cuts to libraries, museums, and the humanities broadly, I fired off a commentary you can read below. Even more, consider supporting your local libraries, museums, or historical societies with a donation and by writing to your members of Congress.

Comments ()