Reading the West by Road

Quick notes from the road's end

Almost three weeks ago, I headed east, away from the saltwater breezes, into the heart of the dry West. After 18 days and more than 5,100 miles, I returned yesterday, less than 20 hours ago. I'm road weary, and when I sat down to produce this essay, clarity was missing.

The places I traveled to and through largely failed to conform to idealized notions of landscape and economy that were established mainly in the early to mid-19th century. When American legislators created land policies to guide the colonization of the continent, they expected small scale farms to blanket the nation in self-sufficiency, properly seeding a virtuous republic.

On the land, evidence of this vision working is scant.

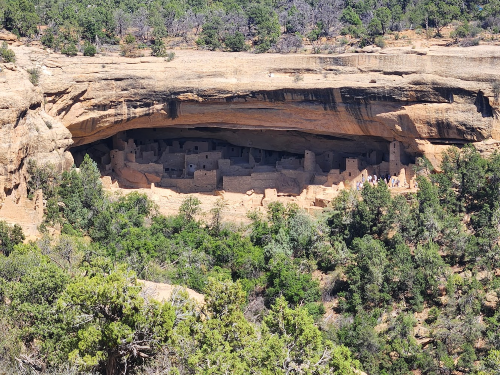

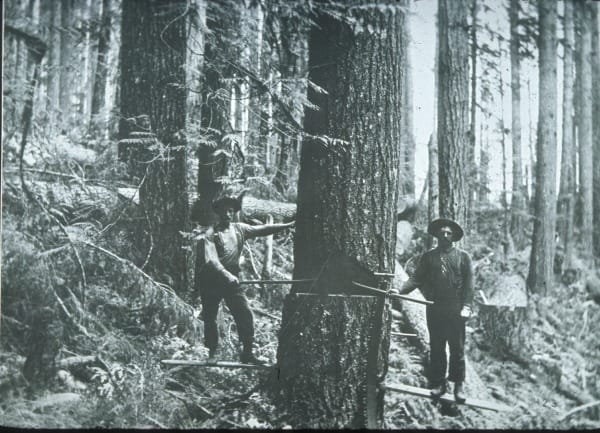

After wresting territory from the existing inhabitants, this land policy, best represented by the Homestead Act (1862), worked some places for some time but foundered in much of the West. Although Native people figured out ways to make good lives in all corners of the West, the newcoming Americans adjusted but often failed. Land too steep, too dry, too treeless, too hard to get to, made sure the founding vision remained unrealized.

Two responses were common.

First, lawmakers passed new legislation to adjust to the perceived inadequacies of their earlier policies to expand land bases or to subsidize irrigation or to encourage tree-planting.

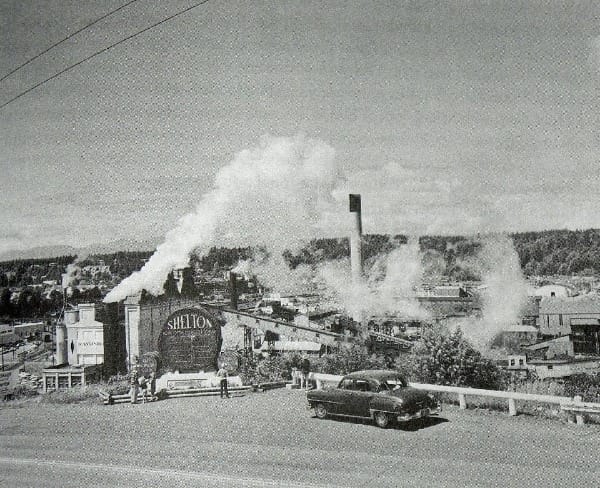

For decades, I taught about these policies and their shortcomings, how political planning found a difficult match with the West's ecology. But teaching isn't the same as seeing. If the vision had succeeded, our road trip would have passed farmhouses regularly on the rural roads and state highways we drove. Instead, we passed miles and miles of land without a farmhouse or community in sight. A series of 160-acre homesteads stamped uniformly across the continent was always a fantasy, but this ideal has informed American mythology and possesses great staying power. We need to be more critical and accurate and recognize that geographical realities meant uniform land policies were always bound to fail in a diverse landscape.

Second, legislators and administrators enacted conservation programs, such as creating national parks and national forests in public ownership.

This conservation response is more visible. Literal signs mark when you are entering/leaving a national forest and shacks for fees sit on national park borders. Spending so many of my days over the last three weeks in and near these places drove home their value. That value, however, primarily rests in conservation and cultural realms, not traditional economic activity (although the parks certainly generate plenty of revenue from typical commercial exchanges as the development outside, say, Zion National Park demonstrates). The geography of the Great Sand Dunes or Grand Canyon did not lend itself easily to either subsistence or money-making enterprises on much of a scale. Here, unlike most places across the nation, maximizing production did not reign.

During the many hours on the road, I kept thinking about the legacies of the 19th century. I felt how ineffective a uniform standard has been. I noted the need to adapt and noticed the failures when adaptation was not forthcoming. I saw land hammered into submission looking beaten. The emptied barns and homes suggested stories of hard times and broken dreams.

Yet signs were not only bleak. I drove through beauty. I saw places where generations have made good lives. And I know that what sustains them is diversity—of place, of practice, of attention to local detail.

Comments ()