Respites in War

National parks in World War II

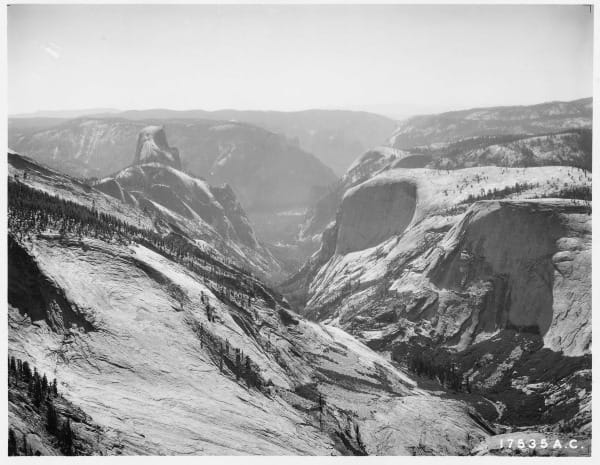

Starr West Jones asked rangers at Yosemite National Park about good places to hike. Together they devised a two-week plan, and then Jones headed out alone.

At Fernandez Pass, when he looked across vast distances, Jones became reflective and looked within himself, something that being in nature often prompts.

"Doubts and fears have slipped from me and standing here alone upon the heights I know a peace of mind which will follow me always," Jones wrote in his field journal.

Peace of mind likely weighed heavily on Jones. He was an Army sergeant, and it was 1942. Finding ways to remove doubts and fears while in nature offered a small salve at a critical moment in both Jones's own life and global history.

Jones's experience wasn't unique. National parks offered many a respite during war.

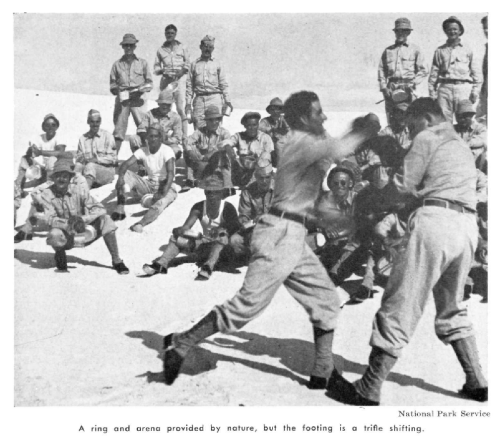

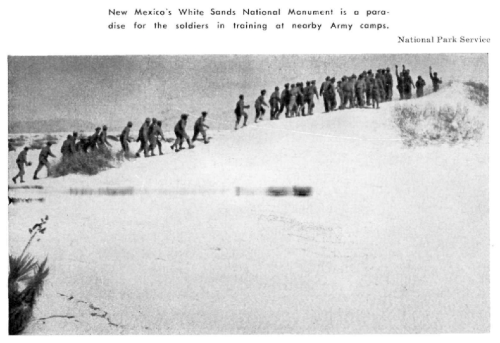

At White Sands National Monument (since 2019 a national park), soldiers recreated often, sometimes with family converging at the site for quick visits. In this "land of spectacular scenery, beautiful coloring, [and] unusual sights," young men raced up the dunes and slid down them before launching into horseplay as a relief from their training. The bombing range that bordered the monument to the north meant the sounds of war touched down too. Still, the sands offered a break. Before heading back to base, an enlisted man was overheard saying, "This is my third time here, and I'm coming again whenever I get a chance."

According to one 1944 account, almost 30% of park visitors wore the nation's uniform. During the war, the National Park Service opened the parks and monuments to uniformed Americans free of charge.

The ranger at White Sands said the reason for this generosity was because the National Park Service felt "that its system is one of the institutions of our 'American Way of Life'" that the soldiers were defending. A colonel explained to the troops he led, "National parks really help you understand the nation."

That may have been true, but the National Park Service knew it faced a balancing act in the dual responsibilities it felt during the war. On the one hand, it would support the war effort. On the other hand, it had to protect the federal estate so that "untamed America" would last beyond the war. That wildness, after all, offered one of the "compelling influences that produced the nation we are fighting for today."

By 1944, the Park Service had roughly 700 agreements for cooperation with the war effort, the most appealing of which allowed the agency to "minister to the health and comfort of the uniformed men and women who have come to the parks for rest and recreation."

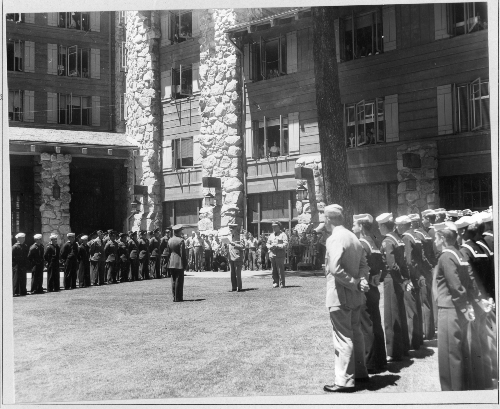

Some of those occasions were day or weekend trips like the one to White Sands. But at Yosemite, the Ahwahnee Hotel briefly became a US Naval Convalescent Hospital, good for 600 recovering sailors. The McKinley Park Hotel in Alaska provided a place for soldiers to escape to on leave from duty in the Aleutian Islands. On the East Coast, several park sites offered soldiers, including some British ones, a chance to catch their breaths.

Recovering Americans sometimes found themselves well off the beaten path. A wounded aviator journeyed all the way to Dinosaur National Monument. Limping around Dinosaur Quarry, the officer saw the rich trove of fossils and was impressed, even though only a temporary museum held exhibits.

As he left, he encouraged the Park Service employees who were struggling with temporary quarters. "You take care of your job," he told them, "and I'll see if I can't take care of mine so you fellows can do yours."

The sense of shared duty across such stories is striking.

Given the stakes of the war, national parks might not deserve special attention. In fact, some considered closing them as a cost-saving measure. However, a former ranger named Beverly Blanks disagreed.

Blanks had left the Park Service to enlist. Writing to his former superintendent, Blanks confessed he "had no conception of how much the national parks could mean in wartime until I came here."

He continued:

If you could hear the men talk of our parks and forests, you would know how great a part they play in the American scene. When talk turns to "before the war", it's invariably the days in the woods, the hours spent with rod and reel on lake and stream, the camping trips and the quiet nights in the pine woods that take up most of the time. And it is those things that these men are fighting for, as well as for their homes, sweethearts, wives and families.

Blanks shared this because initially he thought the parks should be closed down during the war to save money given the enormous burdens of war. But time led him to believe he was "dead wrong."

What I didn't know was what stress and strain these men and women in the army and in war work were going through. Without some outlet, people can't stand up under this life without cracking. What they need is recreation areas where inspiration combines with relaxation to give a new lease on life and new hope for the future.

The Park Service readily stood by to help however it could with a significantly reduced ranger force. Just before Pearl Harbor, the national parks employed almost 6,000 people; by D-Day, it was barely 1,500. Meanwhile, visitation shrunk over a similar period by nearly two-thirds.

Nevertheless, the Park Service and its allies knew that these "priceless areas" would be "more desperately needed tomorrow." Park advocates looked ahead to ensure the parks remained protected; they were confident in victory and knew that the peace of mind Jones felt in Yosemite and the inspiration and hope Blanks recognized could not be sacrificed.

Comments ()