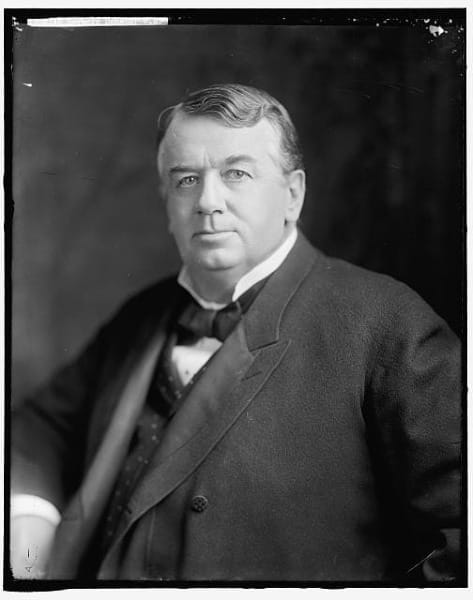

The Unexpected from Senator Weldon Heyburn

Beyond conservation's leading foe

For a historian, a writer, any person, it is good to be surprised and have prior views complicated.

When I set out to research this week's essay, I knew the basics of the story I wanted to share. I gathered the evidence I had available and collected a bit of additional research online. My basic memory of the story held. But then, I discovered an element that stood out quite unexpectedly. I had to learn more.

Here is the story I planned to tell:

Weldon Heyburn served Idaho in the US Senate from 1903 until his death in 1912. Heyburn built a career and influence as a mining lawyer in Wallace in the heart of Idaho's silver mining district.

For the most part, Heyburn did not distinguish himself as a legislator. He supported mainstream Republican policies but typically rejected the progressive wing of the party (the one exception was supporting the Pure Food and Drug Act) .

In particular, Heyburn opposed national forests quite ostentatiously—this is what interested me.

Heyburn called Gifford Pinchot, the nation's chief forester and most dedicated proponent of public forestry, Czar Pinchot. In criticizing the Theodore Roosevelt administration's conservation policy—his own party—Heyburn said, "Government by policy belongs to kingdoms and empires, not to republics!"

Reading his century-old words, you encounter the type of hyperbole that would have attracted great attention during our own social media age.

When debating the Weeks Act, a law that allowed the federal government to protect watersheds by acquiring cutover land primarily in the East and authorized funds for states with fire protection plans, Heyburn claimed it the "most radical piece of fancy legislation" ever considered in Congress, the type of overstatement that the senator employed without thinking twice.

Such comments, which could be listed 10 times over, paint a picture of Senator Heyburn as something of a conservative, even a reactionary. He plotted to starve the Forest Service of funds and to rob presidents of their statutory power to create forest reserves in the future. The writer Timothy Egan uses Heyburn as a foil to Pinchot in his account of the 1910 fires in Idaho and Montana, the perfect embodiment of anti-conservation.

That's the story I planned for this week. It would show how some politicians have always opposed conservation of the nation's common resources. And many of them, like Heyburn, were corrupt (he seemed to have kept up his law practice using inside information) and, to my way of thinking, often odious in their obstructionism.

But this time when I encountered Heyburn, I discovered another side that I found far more interesting and even admirable. (I type that with some anticipated regret.)

Heyburn had been born in 1852 and raised in Pennsylvania in a Quaker family. Too young to fight in the Civil War, Heyburn nonetheless felt the impact of Gettysburg.

Representative Burton French from Idaho memorialized Heyburn by noting that he was "loyal to the Union" with "absolutely no patience with the causes that led up to the Civil War and was, in fact, bitter toward every movement that looked to the perpetuation of even the memory of that unfortunate crisis in American history." French located that steadfast, burning-hot antipathy in Heyburn's close connection to Gettysburg.

The reason French mentioned the Civil War nearly 50 years after its conclusion is because Heyburn had numerous opportunities to raise his ire, because the Confederacy may have lost the war but it was never defeated in American culture.

Heyburn consistently railed against any federal or party support of the Confederacy—something that too few politicians, then and now, could manage.

Even seemingly mild things riled up Heyburn.

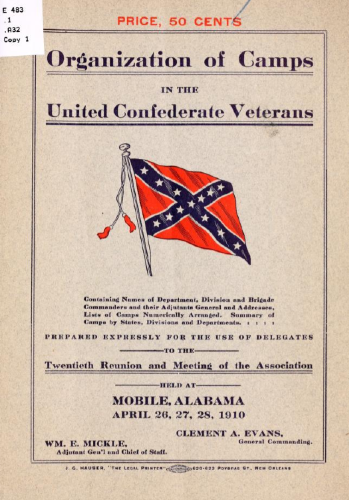

In 1910, Congress passed a resolution that authorized the government to loan tents and camp utensils to a reunion of Confederate veterans in Mobile, Alabama. Heyburn learned that the veterans would wear the Confederate uniform and the Confederate flag would fly over the ceremony (along with the Union flag). In a speech that closed in on an hour, Heyburn asked his colleagues if their whether their consciences would be stirred if "the rebel flag shall again wave over the property of the Union."

Then, as now, a senator's conscience was cheap. All senators but Heyburn voted to allow it.

Wrapped up in that speech was something that had festered a little longer. In 1864, amid the Civil War where Union forces faced off against traitorous rebels who were intent on maintaining a slave-based society, Congress created Statuary Hall inside the Capitol. Every state had the opportunity to honor two citizens.

Eventually, Virginia, home to James Madison (primary author of the Constitution) and Thomas Jefferson (primary author of the Declaration of Independence), chose George Washington and Robert E. Lee to represent the state. Heyburn wondered whether Congress in 1864 could have ever imagined a state adding "the statue of Benedict Arnold in that hall," accurately and deliberately recognizing Lee as a traitor to the United States.

While chastising his colleagues for loaning federal tents over which Confederate flags would fly, Heyburn brought up Lee again. According to the New York Times, Heyburn "begged" Virginia to take down Lee who "while dear to the South is not dear to us."

Take it away and worship it if you please, but do not intrude it upon the people who do not want it.

Later that year in Seattle, Heyburn attended what the New York Times called "a sort of Republican love feast." Heyburn rose up and demanded the band stop playing. It had been playing "Dixie," and Heyburn had had enough.

This is a Republican meeting, and we want no such tunes here.

The meeting ended. "No clasping of hand across the Bloody Chasm for Heyburn," reported the Times.

In his memorial to Heyburn, Representative French said the senator was "intolerant toward the memory of the movement that looked to the breaking asunder of our Nation as were those who fought for the Nation's integrity uncompromising and intolerant in their position 50 years ago."

Representative Clarence Clark of Wyoming claimed Heyburn "formed his own opinions and held to them with a consistent and unusual tenacity."

Heyburn's congressional colleagues recognized that Heyburn had not forgotten the unforgivable.

When I encountered that determination in his opposition to conservation, I found it mulish and irritating. When I see it in his rejection of the Confederacy and its persistent resurfacing, I find it more commendable and principled.

The Lee statue in Statuary Hall came down in 2020. But Confederate General Albert Pike, whose statue was torn down during 2020 protests, is now going back up in Judiciary Square in Washington, D.C., an effort to fulfill the appalling Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History executive order signed last March.

In 1910, even a conservative Republican western senator understood there is no place for Confederate memorializing in a Union. What will it take in 2025?

Comments ()