"They had their bearings"

And keeping ours in a new technological age

"They had their bearings."

This sentence jumped off the page when I encountered it last week. I've been musing about it ever since.

When I took the name Taking Bearings for this newsletter, I was thinking about the actions we can take to help us understand our place. Taking my bearings seemed like an ongoing project, a way to sink into place with a deep dose of history informing it all.

This is largely how I move through the world, observing a place and reckoning with its history. As I deepen my knowledge, which can come both from immersion and from study, I grow more settled into a landscape.

Lately, though, I've felt unsettled. Last week's essay says as much, when I pondered the pace of destruction of public lands this White House has pursued. I rely on these lands as an important touchstone. Journalist Michelle Nijhuis spoke for me last week in the New York Times writing, "Those who wish to abandon the experiment of the public lands may see them as simply assets on a balance sheet; the rest of us know that they are, above all, the landscapes that hold us together."

Political incompetence and mendacity are not the only reasons for my recent unease.

Technological change is dizzying as AI's promoters and condemners compete with audacious predictions about how "everything" will soon change, faster than anyone is ready for. None of this even considers the climate and biodiversity crises or economic calamities or public health worries or a host of other things that contribute to a sense of a universe speeding out of control.

Against all of this is that simple sentence that plucked at my attention:

"They had their bearings."

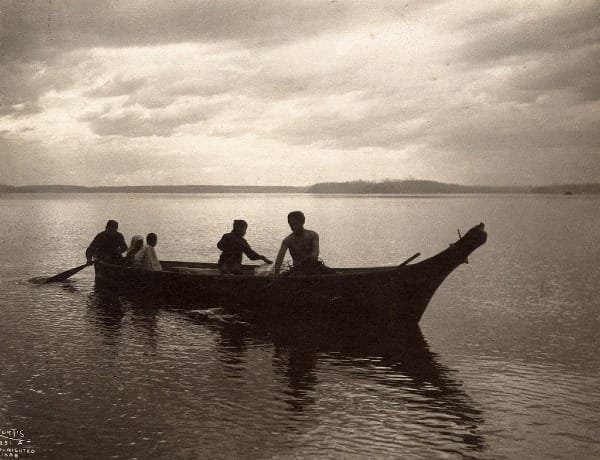

The sentence is the characterization writer and legal scholar Charles Wilkinson drew about the Lummi Nation in his book Treaty Justice: The Northwest Tribes, the Boldt Decision, and the Recognition of Fishing Rights (2024). Wilkinson emphasized the assurance the Lummi possess, knowing who they are and how to live well in a place.

Like anyone else, Lummi life included disruptions in the millennia they have lived on the Salish Sea, but they knew who they were largely because they knew where they were. They had their bearings. They knew which foods belonged to which seasons, which place contributed to community well-being, which stories brought good and ill fortunes, which practice of generosity cemented obligations and responsibilities.

Having your bearings means looking around and seeing familiar, useful things and knowing how to act. It is perhaps synonymous with being truly at home in the world.

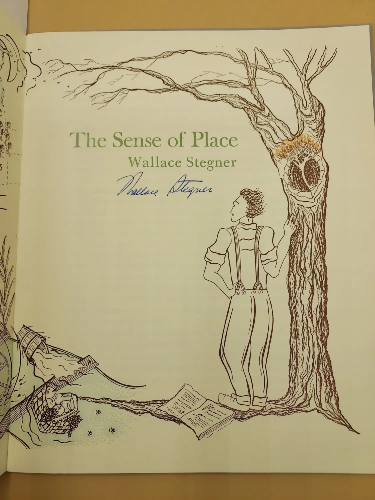

According to Wallace Stegner, Wendell Berry once said that if you don't know where you are, you don't know who you are. Ralph Ellison said something similar in Invisible Man (1952), but in environmental circles it is Berry's version via Stegner that gets quoted. What Berry was saying, with Stegner's full-throated approval, was that we need to be placed, rooted.

In other words, we need to have our bearings.

Stegner went on in the essay, titled "The Sense of Place" (1986), to explain, "a place is not a place until people have been born in it, have grown up in it, lived in it, known it, died in it—have both experienced and shaped it, as individuals, families, neighborhoods, and communities, over more than one generation."

Berry, of course, exemplifies this notion as he has spent most of his life in Henry County, Kentucky, near the Kentucky River while creating a fictional universe in the same neighborhood in his Port William novels and stories. As he is with most things however, Berry is an exception. Such deep rootedness is unusual in 2025.

Berry described how he used horses instead of tractors to farm the hills of his family home in "Horse-Drawn Tools and the Doctrine of Labor Saving" (1981). He argued against technological determinists. Berry insisted that we have a choice in what technologies we use when we are willing to limit our desires and the size and type of technologies we employ. "Without that willingness," Berry asserted, "there is no choice; we must simply abandon ourselves to whatever the technologists may discover to be possible."

This reminds me of the current AI enthusiasm. We must use it lest we be left behind, goes a common refrain today, and people scramble to incorporate it into workflows or to advance their education or unlock new levels of productivity and profit.

But these techno-enthusiasts don't have their bearings. Theirs is an exciting world without precedent. But being "without precedent" is another way of saying they are unmoored, unsecured in a world without place, without a past, without a moral foundation.

For his part, Berry concluded that "machines should be adapted to us—to serve our human needs as our history, our heritage, and our most generous hopes have defined them." When we have our bearings we can make wise choices about adoption or restraint.

If the Lummi knew their bearings as Wilkinson said, they did so in part because their place-based culture maintained historical continuity.

"Legends were one of the most important teaching tools," according to Pauline Hillaire, a Lummi historian, in Rights Remembered: A Salish Grandmother Speaks on American Indian History and the Future (2016). "We listened, and we calculated the behaviors of the characters and the intentions of the legends. We interacted with the environment in the place where the legend originated, and we had time to think through the philosophy used by the characters within the legends. We had the time, space, and opportunity to act out the legends we heard."

I read this as tying bearings to place and through tradition informed by values appropriate to past experience. This is how Stegner defined place. And in seeking to maintain fidelity to place, this is how Berry chose which technologies to use and how.

If we adopt a placeless AI universe as our home with the future being the only time that matters, we will be lost.

In Other Words

- Last week, paid subscribers received the profile shared below. Free subscribers can read a preview. Upgrading your subscription not only grants you access to interviews like this but also helps support my work.

Comments ()