Tracking Forests

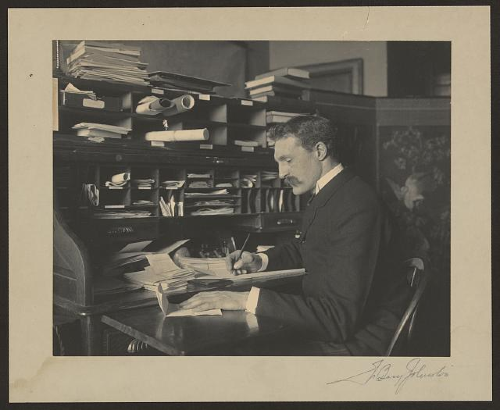

Charles Sprague Sargent among Washington's trees

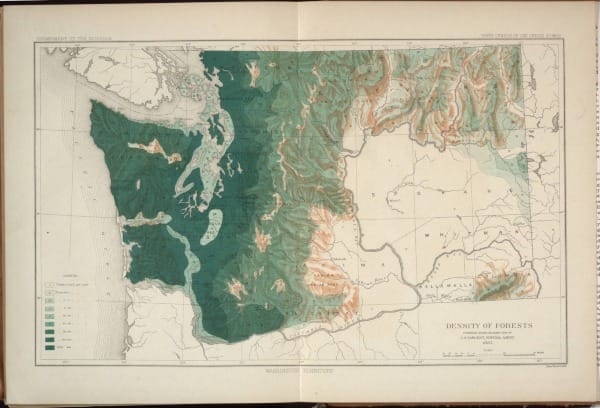

Last week, my wife returned from a meeting talking about the interesting design choices at the University of Washington, Tacoma, campus. In particular, she shared a fascinating map showing the density of forests in Washington from 1883.

A bit of searching and the origin of the map was revealed: Report on the Forests of North America (Exclusive of Mexico), volume 9 in the 1880 Census, published in 1884. Charles Sprague Sargent directed the report along with this and other fascinating maps.

Sargent played a key role in forest conservation that I briefly discussed in my last book. But the map made me curious to learn more, especially what he said about Washington forests.

Personal Background

Sargent came from an elite family, ensconced just outside Boston on a large estate with gardens and parklands. He graduated from Harvard College right as the Civil War ramped up. Sargent served the Union, fighting against the traitorous Confederacy.

Afterward, Sargent became the director of Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum, a role he kept for a whopping 54 years. He also started the magazine Garden and Forest, a small but influential journal that published about conservation matters.

Sargent’s position at the arboretum oriented his way of thinking about forests. As a botanist, he thought about trees more than forests. Frequently in history books that mention Sargent, authors use the old line about not being able to see the forest for the trees in describing Sargent’s view. This was unsurprising given the time, because while botany enjoyed a long tradition in the United States, forestry had not yet truly begun.

Nevertheless, Sargent became an expert in North American trees, an essential prerequisite for thinking about forests. He also could be irascible, egotistical, dominating, and a bit touchy — traits often found among the elite who expected to get their way.

Census

The Constitution requires censuses. Most people rarely think about them, and when they do, they mostly think about counting people. But censuses track other things as well. Historians have used them to great effect at painting a partial view of the nation, because often they count the same information across 10-year intervals.

Being asked to prepare a report about forests for the 1880 census, Sargent took to the task seriously. One historian characterized it as “an epochal study in plant taxonomy.” Another noted Sargent’s work was “impressive.” It drew special attention to how fast timber companies had destroyed Midwestern forests.

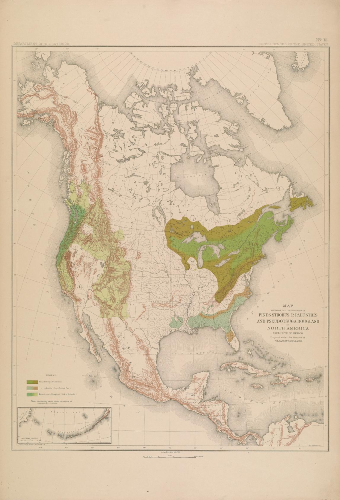

The report also included an accompanying portfolio with 16 continental maps that show the distribution of various tree genera that create fascinating (and often pretty) viewing.

The Report on the Forests of North America topped 700 pages that consisted of a huge tree “catalog” along with some analysis of the economic value of trees, arranged geographically.

That’s what gets us to Washington.

Washington Forests, ca. 1880

Sargent presented a clear portrait of the Evergreen State.

Western Washington included “the heaviest continuous belt of forest growth in the United States,” Sargent wrote.

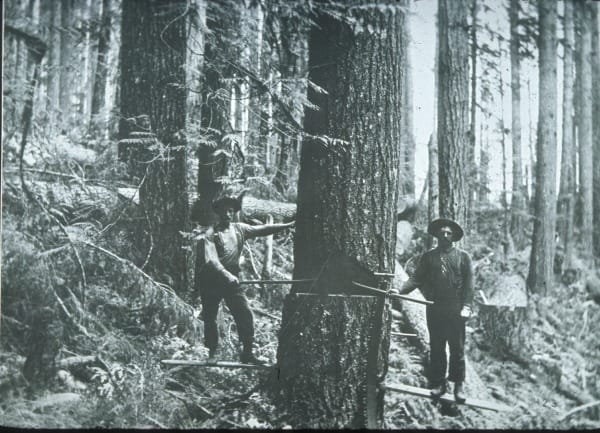

Except for the Cowlitz and Chehalis River valleys and a plain near Steilacoom, trees of western Washington were coniferous, 7/8 of it Douglas fir in Sargent's estimation. As you moved up the Cascade Mountains the species differentiate a bit more, but he dismissed them as “of little economic importance.”

On the east side of the mountains, forests were scattered along mountain ranges. “The great plains watered by the Columbia and Snake rivers are entirely destitute of tree covering,” read Sargent’s not cheery assessment.

Sargent did not have enough data to estimate the total timber standing in the territory, but the merchantable timber in western Washington was “enormous.” He believed 200,000 board feet per acre was “not at all exceptional.” That is roughly enough to build 10 decent homes, per acre.

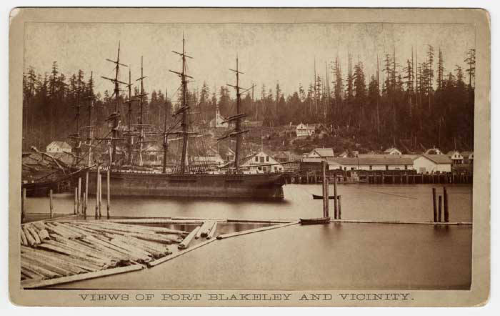

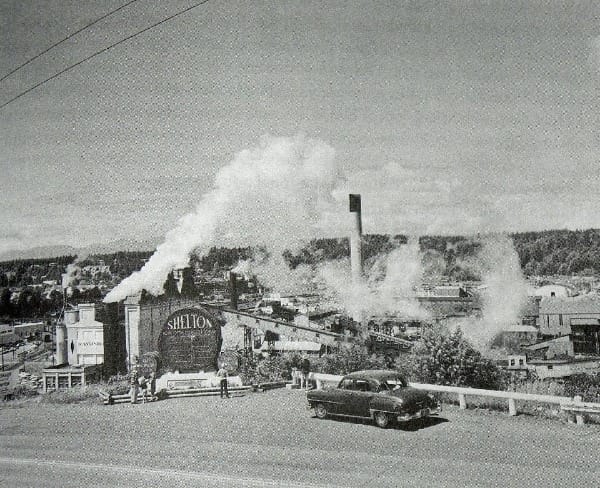

Along major waterways — Puget Sound, the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and the lower Columbia River — the best trees from one to two miles had been “culled” already “to supply the important lumber-manufacturing interests” in Washington.

What that added up to was significant. In 1880, Sargent tracked “153,986,000 feet of lumber, 6,550,000 laths, 910,000 shingles, and 23,066,000 staves” — an impressive output for a place whose first sawmill appeared just three decades before.

The names of the manufacturing centers read quite interesting from today's perspective, too: Port Gamble, Port Madison, Port Blakely, Port Discovery, Seabeck, Utsalady, Tacoma, and Seattle. Except for the last two, these are not names common to manu Northwesterners. Most are on the western edge of Puget Sound, reachable today only with long drives or ferry rides from where the bulk of Washington’s population clusters along the eastern edge of the sound.

Although Sargent dutifully broadcast the important economic information, what most impressed him was how “wasteful in the extreme” were Washington’s lumbering methods.

Sargent explained:

Loggers cut only timber growing within a mile or a mile and a half of shores accessible to good booming or shipping points, or which will yield not less than 30,000 feet of lumber to the acre. Only trees are cut which will produce at least three logs 24 feet long, with a minimum diameter of 30 inches. Trees are cut not less than 12 and often 20 feet from the ground, in order that the labor of cutting through the thick bark and enlarged base may be avoided, while 40 or 50 feet of the top of the tree are entirely wasted.

Implicit in the data was a contention that with such waste, abundance could turn to scarcity. This was the problem of the age.

A Position of Influence

The place where Sargent appears in the historical record most prominently is not his observations about Washington forests, but how best to protect the nation's western forests.

In 1896, Sargent led a National Forest Commission, sponsored by the National Academy of Sciences. Its task was to survey western forests and assess how best to ensure they survived into the future. Gifford Pinchot found his way onto the commission, and John Muir tagged along as an influential advisor.

By the end of the tour, consensus had not been reached. For some, like Sargent and Muir, western forests needed to be protected — from fire, from vandals, from timber thieves. They advocated the US Army guard the nation’s forests. For others, like Pinchot, forests needed to be managed as a renewable resource that produced economically valuable outputs. That party advocated for a trained group of professional foresters, a forest service. Pinchot swallowed his pride and backed off his criticism so the commission’s report could be unanimous (but regretted that later).

In the quick aftermath, the commission recommended President Grover Cleveland create 13 more forest reserves covering some 21 million acres. Cleveland acted, setting off controversy that eventually prompted Congress to strengthen instructions for managing the nation’s forests.

Pinchot and his Forest Service would carry the day in the long run, but Sargent won that first round. Although few remember his name, Sargent served as one of the most influential conservationists just as that field emerged.

The maps he made and census report he created meant Sargent spoke with authority atop a mountain of data just being compiled.

Comments ()