Violence in the Woods

The pervasive harms in Washington's early timber economy

Once in a while, a memory of a classroom discussion tickles my mind. Sometimes, it is so faint I would be hard-pressed to guarantee it happened if under oath. But enough details form to make me think it’s probably real.

One of these occurred to me recently, a call back very early in my teaching career, a fact I can pinpoint from the classroom setting. The discussion revolved around violence in industry around the turn of the twentieth century.

Here, the fuzzy details get fuzzier. A student may have pointed out that unions used violence, a comment that hinted at blame. I may have pointed out that industrialists had more access to the means of violence and the very way industrialization was arranged meant that workers were subjected to far more violence than striking workers ever managed to inflict.

A new project I’m working on (more details later) focuses on Washington’s forest history, and this gauzy recollection sprung to mind as I have been grappling with the timber industry’s past. Any reckoning with that industry’s early decades requires an accounting of violence.

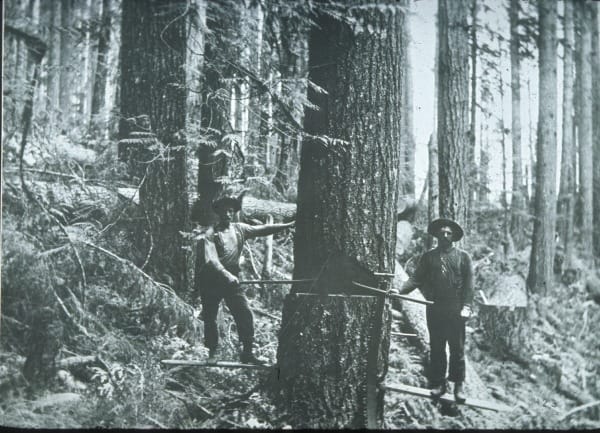

Violence of Work

Statistics tell some of the story.

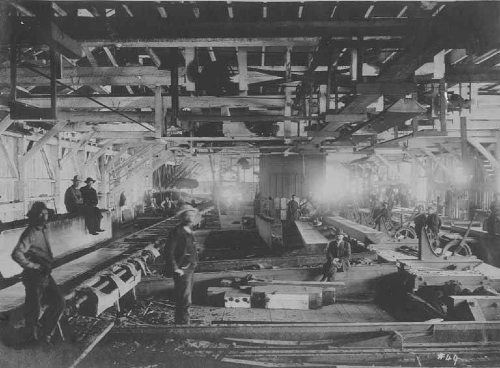

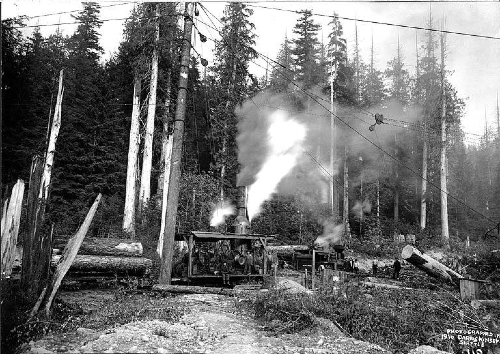

In one five-year period, 1918-1923, 912 people died in logging accidents in Washington. This number does not include those who were injured, perhaps to the point of being unable to work. A few years earlier, in 1914, nearly 5,000 workers were injured in just the first four months of the year. These numbers don't include millworkers either. During the 1920s, 452 sawmill workers died. By the 1920s, mills had been operating for decades, so the deaths likely represent a decrease from the number who died in earlier decades before the state captured statistics. And death statistics do not count the fingers and limbs lost to spinning blades.

So the work itself was violent.

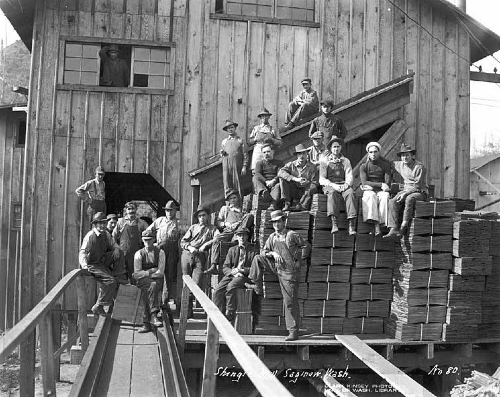

In The Last Wilderness (1955), an account of the Olympic Peninsula I wrote about here, Northwest author Murray Morgan subtitled his chapter on Grays Harbor, a lumber center on the Pacific coast, as “The Era of Violence.” Grays Harbor was not unusual for earning such a description.

Read Morgan or any number of other histories of logging and you’ll find metaphors of war and battle deployed liberally. Such literary devices are useful. Loggers can wage war against the forest. Union men can battle against management. And corporations can counterattack striking workers. Such language was not always metaphorical.

In part because of the violence, unions organized, which timber operators felt as a personal and civilizational affront. When strikes broke out early in the 20th century, violence accompanied them. In Grays Harbor, vigilantes loaded 150 striking woods workers into boxcars ready to ship them elsewhere before the mayor halted it. Others had no such beneficent sponsor and found themselves loaded up and shipped off like cattle.

Broken strikes were accompanied by broken bones.

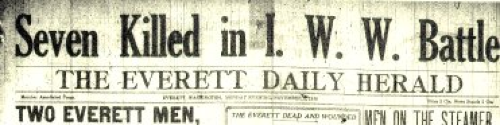

Everett Massacre

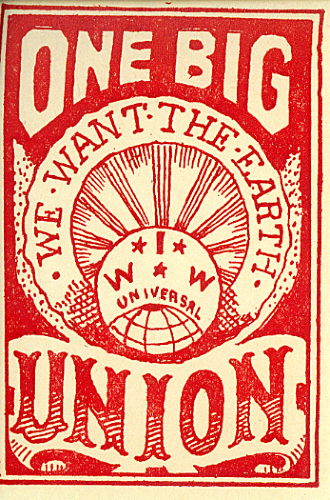

The most notorious example of violence occurred in Everett in 1916 when Wobblies, members of the Industrial Workers of the World, joined with other unions on strike. The Wobblies were more radical than most unions, believing an economic revolution was called for. This made them fierce advocates and favored targets.

“The I.W.W. appealed to idealists who wanted a better world and to outsized juvenile delinquents in corked boots who wanted to smash back at a world they never made,” according to Morgan.

In Everett, tensions had been building all year when millowners did not raise wages despite rising profits and brought in strike breakers, a tactic that often produced violence. The local sheriff Donald McRae repressed labor protests.

Wobblies gained notoriety not only through the labor organizing but also their free speech fights. They’d speak on street corners where police would arrest them. A few years before, the Wobblies won a free speech fight in Spokane where arrested speakers filled the jails and forced authorities to release them and repeal the ordinance that forbade Wobblies from public speaking. Everett, however, still had laws restricting speech on the streets. The sheriff hauled off Wobblies; the city passed stricter laws.

Tensions built.

The night before Halloween 1916, Wobblies came to Everett preparing for another speech showdown. McRae met them along with 200 deputies and told the Wobblies downtown was closed to them. Then, the Wobblies were captured and transported south of town. The Wobblies were forced through a gauntlet, getting beaten by clubs, guns, hoses filled with shot. The bloodletting only deepened each side’s commitment.

The next week, a few hundred Wobblies steamed north from Seattle. The sheriff had deputized hundreds of vigilantes who met the boats. A shot was fired—no definitive answer has ever been established for which side fired first—and a gunfight ensued with much greater fire power coming from land.

When it ended, 10 minutes later, the casualty number was substantial. Two deputies and between 16 and 20 others were wounded in Everett. Between 5 and 12 Wobblies were killed and around 27 wounded on the boats and in water. No one was ever convicted for any of it.

Such showdowns make for dramatic history and the radicalism of the Wobblies, who never shied from fights, make it easy to blame them for ramping up the likelihood of violence. Yet violence pervaded this entire sector. In such a context, violence didn’t need an instigator; it was the air the timber industry breathed.

The Forests, Too

Any account of violence around the woods must include violence to the woods. “The war against the forest went on,” wrote Morgan. And even if loggers didn’t see themselves quite a soldier in such a war, what they left in their wake certainly resembled a battlefield.

Clearcuts, slag piles, eroding hillsides spread through logging country faster and faster. As Morgan simply put it, “Profit depended on speed, and speed on expensive equipment.” Technology increased investments which required more cutting to recoup costs. A cycle ensued that invited no restraint. A local historian published a history of Grays Harbor with an apt title, They Tried to Cut It All—indeed, they did.

Timber work generated great wealth and established many of the towns and cities in a time that seems distant. And with that distance, we can too easily romanticize an earlier way of life. Such as the work of loggers and millworkers—good, honest, working-class occupations.

But the violence was inescapable for those living as part of that world. A wider angle view might temper the romance.

Comments ()