Dislodging a Logjam

President Bill Clinton and the 1993 Timber Summit

During the 1992 presidential campaign, candidate Bill Clinton stopped in Seattle to meet with business and labor leaders. An environmental adviser, Katie McGinty, warned him to not get entangled in the Northwest’s intractable old-growth forest issue. If it comes up, she encouraged him, note its complexity and move on.

The meeting proceeded and no comments about forests and endangered species derailed it. McGinty breathed a sigh of relief before Clinton, as he started to leave, said that he would break the regional stalemate if elected. Later in Eugene, Oregon, he said it again, adding he would hold a timber summit in the region to learn about the issues and potential solutions. Then, he was elected, and McGinty (and others) were faced with following through on Clinton’s excessively optimistic and ambitious promises.

The week that includes Presidents’ Day is a good time to revisit the summit—officially the Forest Conference—which represented a turning point in the forest history of the region.

Clinton walked into a movie well after its opening sequence. By 1993, when he was sworn in, the forest situation was mired in deep mud. Court orders in 1991 and 1992 had shut down most timber sales on most public land in the Northwest. A series of interlocking developments created this logjam.

- Republican-led federal agencies had been interfering with science for years, which violated the law.

- Forestry and wildlife science was becoming more sophisticated and more certain about the role of old-growth forests in supporting biodiversity.

- Biodiversity was threatened because of timber harvesting practices.

- Once the northern spotted owl was listed as a threatened species, activities that hampered their survival became unlawful.

In addition to those developments, three catalysts were at work. First, new and stricter laws about forest management gave the Forest Service (and the Bureau of Land Management in Oregon) less discretion in its management. Second, new and better science demonstrated more and more clearly how species like the northern spotted owl depended on old-growth ecosystems. Third, environmental activism kept pressure on the situation through careful litigation and direct action so that federal agencies couldn’t shirk their responsibilities and the public couldn’t ignore the issue.

The final piece that framed the region at the time of the timber summit was the economic context. This factor was complicated and is often obscured in the telling of the story. American timber companies were shipping raw logs overseas, causing mills to shutter. This practice increased 40% in the 1980s; unions argued that stopping the practice would produce 11,000 American jobs. Mill owners also were retrofitting their mills with technology that automated many jobs, causing large reductions in work forces and often mill closures. In Everett, Washington, for example, Weyerhaeuser modernized one mill and cut the workforce by nearly 45%, while closing three other mills in town. Across the region, mills were closing in the years before spotted owl litigation. Corporate investors sometimes purchased timberlands and companies, rapidly liquidated assets (forests and mills), and then abandoned communities. The worst examples of this occurred in northern California, but the Northwest was not immune.

Despite the complexity of this economic picture, most popular narratives boiled it down to a contest between jobs or owls—just the sort of simplification that can gin up outrage.

Into this ongoing, intricate drama stepped an upbeat and optimistic President Clinton.

People rallied the night before the summit. A concert brought 50,000 old-growth advocates under a banner reading “Stumps Don’t Lie,” and they chanted “Clinton and Gore, Cut No More.” Meanwhile, 10,000 logging partisans counter-demonstrated, while others bought television ads.

The new Clinton administration understood the complexity and wanted to prepare for the summit. It reached out to more than 1,500 organizations beforehand for their perspectives. Doing so and studying the issue, the administration knew solutions would not come easily and that expectations were high.

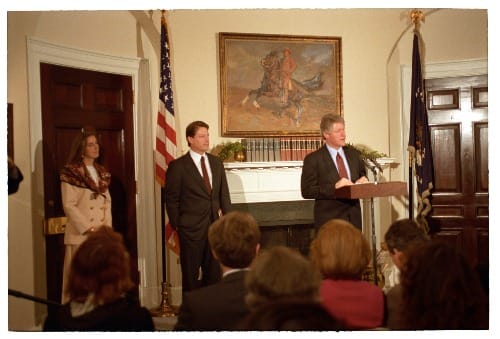

President Clinton not only convened the conference in Portland, but he also brought with him Vice President Al Gore and five cabinet officials. More notable than that, Clinton excluded agency officials. He also welcomed members of Congress to be audience members but didn't allow them to speak.

Sitting at a large oval table, Clinton kicked it off with a few remarks. He promised a new strategy that would move “beyond confrontation to build a consensus on a balanced policy to preserve jobs and to protect our environment.” He promised to listen and learn. He stressed that it was better to be in a conference room than a courtroom. Yet he acknowledged that the process that was beginning “cannot possibly make everyone happy.” Still, he asserted repeatedly that “a healthy economy and a healthy environment are not at odds with each other.”

Then, for nearly seven hours (available here—skip around and watch some exchanges), more than 50 people testified and answered questions. It was a remarkable event and a real feat of focus for those at the table and the audience that observed from the side.

Clinton had not come into the conference blind. His staff had briefed him that the scientific findings within the Forest Service were worse than expected. The northern spotted owl served as an indicator species, a proxy for ecosystem health. Nearly 400 other species were at risk if logging old growth continued apace. Advisers indicated an 80% reduction of cutting was likely required.

At the end, Clinton spoke and tried to set expectations. What he heard that day, the president said, was that ongoing gridlock was the worst option, because it prevented the “ability to work together and to build a sense of common community.” Such common action was not easy in 1993—and it certainly has not gotten easier. Clinton directed his cabinet to develop a balanced policy in two months’ time.

A Forest Ecosystem Management Assessment Team was created, which laid out options in three months’ time—a victory given the complexity of the issue and the tendencies of bureaucracies and committees. Clinton chose an option. The judge said it satisfied the law. And the Northwest Forest Plan went into effect by the end of the following year.

The summit was, in the words of policy scholar James R. Skillen, “a show of executive force.” The details of the assessment, the option Clinton chose, and whether the NWFP solved anything is beyond the scope of today’s essay. More simply, I wanted to illustrate, during the week of Presidents’ Day, how presidents can dislodge a logjam—within the bounds of law and regular order, even for intractable, controversial issues.

Comments ()