On the Nature of Change

Reports of the National Park Service

The National Park Service evolves just as any organization does. Often, change is incremental, a steady year-to-year shifting that becomes apparent only when examined with hindsight. Other times, the shifts seem more dramatic with clear statements pronouncing a new day has arrived.

As I work on my national parks history, I’m keeping my eye out for clear markers of change. Trendlines are easy to spot; obvious junctures less so. Two reports, one from 1963 and the other from 2012, demonstrate these dilemmas of demarcation.

On the one hand, the reports are about specific park policies. On the other, they wrestle with nothing less than the fundamental nature of change in nature and culture. In two generations, the agency went from wanting to hold parks still to embracing continuous change. Today, a backlash bubbles up, desperate to reverse change.

The Leopold Report

Congress protected the first national parks for their scenery. But almost immediately, wildlife became a key part of park preservation.

Yellowstone National Park became a de facto game preserve when hunting was prohibited in the 1880s. This fact helped nurse bison back from extinction’s edge. But combined with the removal of predators like wolves, elk populations grew and grew. Already by the 1930s, observers worried over the state of Yellowstone’s range, which was rapidly deteriorating.

The crisis built.

During the 1961 winter, the Park Service killed 5,000 elk in its northern herd, hoping to reduce the population sufficiently to allow the range to recover.

The public was appalled and demanded answers. So Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall asked the zoologist A. Starker Leopold to chair an advisory board to study parks’ wildlife management policies. Leopold came from America’s first family of conservation, the son of Aldo Leopold whose A Sand County Almanac (1949) more or less created environmental ethics.

By 1963, Leopold and his committee issued its findings in the drably titled Wildlife Management in the National Parks, known thereafter as the Leopold Report. Seizing the opportunity, the committee did more than evaluate existing policies; it asserted a new goal for the Park Service.

The Leopold Report recommended,

the biotic associations within each park be maintained, or where necessary recreated, as nearly as possible in the condition that prevailed when the area was first visited by the white man. A national park should represent a vignette of primitive America.

This statement reoriented the agency for more than a generation.

Although the NPS did not give up its efforts to cater to visitors or to promote recreation, the Park Service pushed instead toward this peculiar “vignette” that promoted a static picture of nature, trying to lock in its appearance at one moment in time. This goal helped justify actions like reintroducing fire and predators into parks—changes to be sure, but changes meant to recapture and preserve the lost moment of contact.

The Leopold Report had its critics at the time—not least from wilderness advocates who thought the Leopold Report justified far too much meddling by the Park Service. And the report could not satisfy all parts of parks—it was nominally about wildlife after all and the majority of park units concerned people and history. Still, it hovered over the system for decades, while times changed.

Leopold Revisited

In the 21st century, the Park Service scanned the horizon and saw different crises and its director, Jonathan Jarvis, asked for an update. Revisiting Leopold: Resource Stewardship in the National Parks appeared in 2012.

Revisiting Leopold included no notable turns of phrase like “vignette of primitive America” to cement its legacy in the public’s mind. Its priority recommendation read, frankly, like the committee report from 2012 that it was:

To steward NPS resources for continuous change that is not yet fully understood, in order to preserve ecological integrity and cultural and historical authenticity, provide visitors with transformative experiences, and form the core of a national conservation land- and seascape.

Accelerating global environmental change and “an increasingly diversified, urbanized, and aging population” had radically transformed the context in which the NPS operated. Its emphasis on “continuous change” offered an important contrast with its predecessor.

Too, “cultural and historical authenticity” offered something entirely absent from the Leopold Report. In the report’s introduction, the authors note that the nation’s “cultural values and interest” since 1963 had “greatly broadened” which requires greater diversity to maintain relevance. The “authenticity” concept is murky, but it’s an attempt to ensure the parks interpret history accurately and to expand the parks to be relevant to “underrepresented minority groups and communities.”

The need for this broadening was undeniably true. Not until 1995(!) were visitors to Fort Sumter, the site where the Civil War started, greeted with history that stated that slavery was the core issue of the war. The Park Service obviously faced a backlog of work to do—from rectifying biodiversity loss to rectifying diversity blindness.

If the Leopold Report announced an intention to preserve things in amber, then Revisiting Leopold announced an intention to reckon with change—changing climate, changing science, changing demographics.

But some change is, apparently, intolerable.

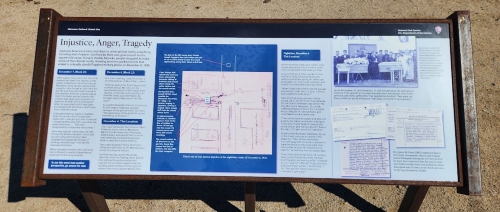

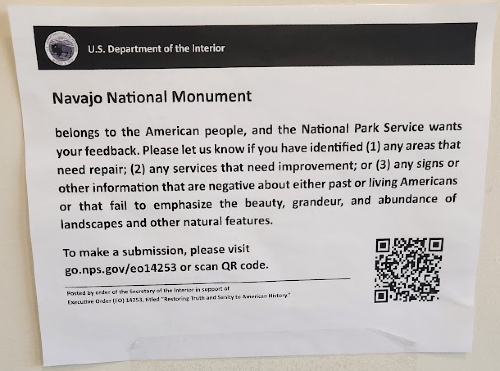

This year, signs have been removed at national parks that that are deemed “inappropriate;” websites have been scrubbed; and bookstores are being reviewed and books removed.

Every year, on certain days, the national parks are open with no admission fee. In recent years, these fee-free days have included the first day of National Park Week and National Public Lands Day, along with Martin Luther King Jr. Day and Juneteenth, in the spirit of Revisiting Leopold’s effort to keep the parks relevant.

Not next year. MLK and Juneteenth have been canceled, but Flag Day/President Trump’s Birthday (June 14) will be celebrated with fee-free entry at public lands. Never subtle, the administration aims for a national park system that cannot accept change.

Comments ()