When Forests Became Habitat

How the National Forest Management Act (1976) Promoted Ecosystem and Democratic Thinking

The Endangered Species Act (1973) sparks off the page. Endangerment generates some inherent drama. By contrast, the National Forest Management Act (1976) could hardly be calculated to make eyes glaze over faster. Nevertheless, beneath the prosaic name, the NFMA has been consequential, potentially as revolutionary as the ESA but not nearly as well known.

What prompted the NFMA, what it entails, and how it was implemented shines light on forest management, of course. And there’s important information in that story—especially about seeing forests as more than lumber and pulp. But the NFMA can be seen usefully as the last in a line of reforms spreading from 1960 to 1976. That period reshaped American natural resource policy and reflected a broader revolution not only in thinking and policy but in democracy.

The NFMA, celebrating 50 years in October, merits attention and rewards curiosity.

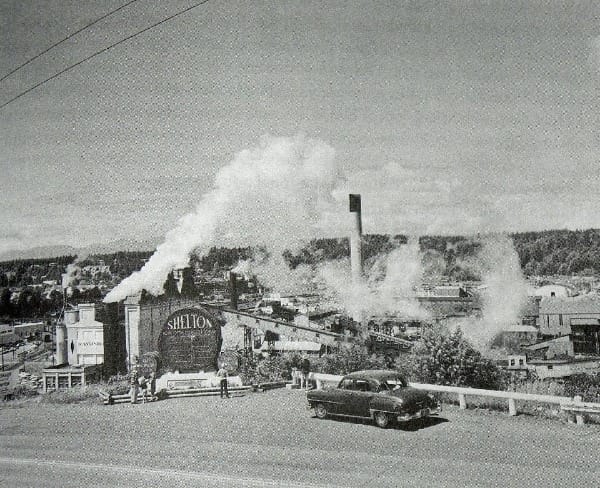

When they were created at the turn of the 20th century, national forests had promised a nation a supply of timber in perpetuity under careful management. For most of its first four decades, the U.S. Forest Service served as a custodian. It sold some timber, allowed livestock grazing, and tried to protect watersheds.

After World War II, the agency reoriented toward maximum production. Timber companies looked enviously at national forest timber, having exhausted much of the privately held forests. So, federal timber sales grew and grew.

On the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in southwest Washington, the Forest Service increased its timber sales from an average of 100 million board feet in 1947 to more than 400 million board feet in a mere two decades. (Before the war, it averaged 8 million board feet.)

To achieve this radical growth, roads penetrated deep into forests where loggers attacked new forest stands with their chainsaws, leaving clearcuts in their wake. After a couple decades of this assault on public timber, members of the public raised alarms.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, national controversies erupted in West Virginia and Montana about clearcuts. A lawsuit effectively ended clearcutting on the Monongahela National Forest. The court relied on an 1897 law that limited what kind of trees could be removed and how to manage that removal. If that law had become an anachronism, the court said, then it was up to Congress to change it.

In Montana, rather than a lawsuit, a critical report from university foresters prompted reactions. With choice words, the report showed that the Forest Service paid little attention to any values other than producing timber, despite laws requiring multiple use. The authors pointed out frankly that multiple use did not exist on the Bitterroot National Forest. It wasn’t entirely the Forest Service’s fault: Congress, the executive branch, and budget process all conspired to more or less demand the agency promote widespread clearcutting (and the agency did not put up a fight).

Congress stepped in.

During the debate in the Senate for what became the NFMA, Hubert Humphrey noted:

The days have ended when the forest may be viewed only as trees and trees viewed only as timber. The soil and the water, the grasses and the shrubs, the fish and the wildlife, and the beauty of the forest must become integral parts of the resource manager’s thinking and actions.

This simple contrast was the nub of the argument, but Congress forced the Forest Service to reorient and reform further.

The law limited clearcutting, yet it included “loopholes large enough to drive logging trucks through,” according to the historian (and my friend) Paul Hirt.

Besides nominally restricting clearcutting, the legislation directed the Forest Service to “provide for diversity of plant and animal communities.” A few years later, when the Forest Service adopted rules for implementing the NFMA, it adopted a conservation biology concept: minimum viable population. The rule stated that “fish and wildlife habitat shall be managed to maintain viable populations of existing native and desired non-native vertebrate species in the planning area,” a requirement that has since spawned scores of lawsuits and forced forest management to act in fundamentally different ways.

Under this, a forest was habitat, first and foremost. As simple and logical as that statement might seem, it reordered how many saw forests, including the Forest Service. A tree farm or industrial tree plantation or a clearcut provided something fundamentally different from habitat.

The NFMA initiated a new set of planning procedures, too. It intended each national forest to create a plan across a national forest and update it regularly (i.e., every 15 years or so). This would ensure minimum viable populations were thriving, as well as other stated goals, such as timber sales or reforestation.

To accomplish this regular planning, the Forest Service needed to change who it hired, because the law required a multidisciplinary approach. The agency in 1976 employed many silviculturists who knew how to grow trees and tons of engineers who knew how to build roads. It didn’t employ that many wildlife or fisheries biologists who knew how to investigate animal populations and their needs.

When you change personnel, you change the perspectives around the table and enlarge what you are able to see and do. (This goes for diverse human experiences, too.)

This planning process also furnished the public ample opportunities to weigh in. These opportunities for public participation grew after World War II and especially after activism in the 1960s that profoundly expanded democratic participation in American public life.

With this procedural shift—that is, opening the planning process to public feedback—and the substantive change—that is, requiring minimum viable populations—the NFMA opened Forest Service management to all sorts of lawsuits, most famously those that shutdown timber sales on national forests in the Pacific Northwest because of the northern spotted owl (which I wrote about here).

By connecting forest management to clear ecological goals and providing places where the public could intervene, the NFMA offered objective improvements. It is easy to declare victory.

However, not everything works out as planned. Since its passage, it can sometimes seem that the Forest Service’s raison d'être is planning. Seemingly endless drafts and hearings and revisions can stymie action. Planning can be a stall that prevents progress.

Also, because the rules governing planning can be altered administratively (i.e., without congressional authorization), critics charge this still gives the agency too much power and insufficient accountability—which was part of what Congress was trying to solve 50 years ago.

The NFMA isn't perfect, yet it stands as a significant landmark—despite its prosaic name—in the evolution of American resource policy.

Comments ()