When War Knocked on the Wilderness Door

World War II and the North Cascades

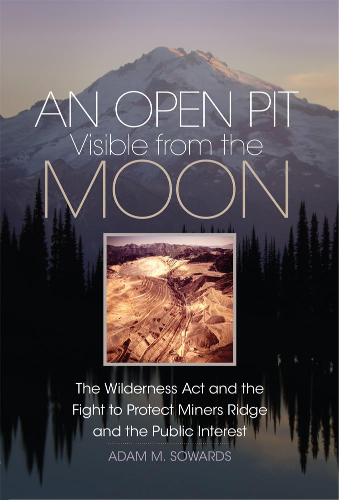

The Great Depression trickled on, a decade and counting. Hitler had already started World War II. Yet in the North Cascades, the U.S. Forest Service and wilderness advocates debated whether to build a road to reach the “mineral values” in a ridge above the Suiattle River.

Hundreds of thousands of acres in the surrounding national forests were protected from commercial development, but Miners Ridge, which contained a fair bit of copper, knifed into the wild landscape. From it, Glacier Peak appeared glorious, reflected in Image Lake, with iconic beauty. This view and the magnificence it evoked made it a feature of the North Cascades’ wilderness values.

Such beauty can seem fragile.

C. M. Granger, the acting chief of the Forest Service in 1940, told Robert Sterling Yard, the president of the Wilderness Society, that good forest administration required him to exclude the mineral areas from any designated wilderness. Keeping the mineralized mountains segregated from the scenic mountains would keep the wild places safe from invasion, said Granger. Draw lines around the potential mine, so went the logic, then there would be no conflict.

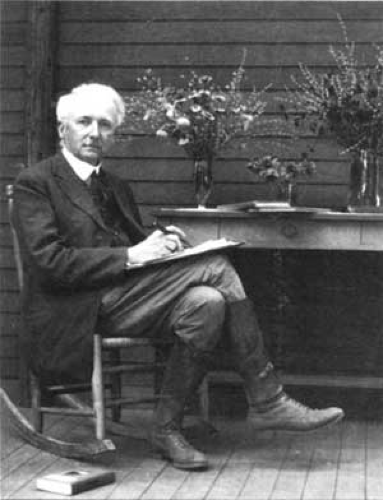

By now an elder statesman among wilderness people, Yard carried himself with gravity over these issues. Among Yard’s fellow co-founders of the Wilderness Society was Bob Marshall who had hiked through the Glacier Peak area the year before on behalf of the Forest Service. Then, shortly after, Marshall died in a crushing blow to the wilderness cause.

Marshall “had so set his heart” on preserving all of the North Cascades in wilderness, Yard implored Granger, that the Forest Service owed it to him to carry forward his wishes.

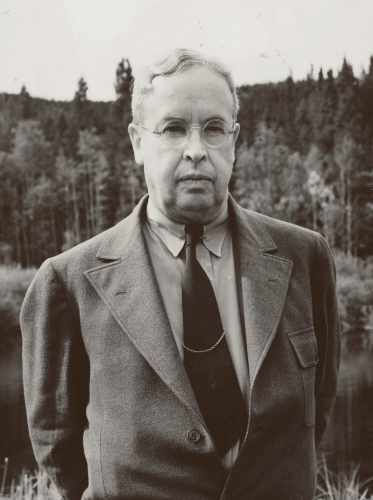

One of Yard’s allies, Irving M. Clark a Northwest conservation stalwart in the Mountaineers, said Forest Service Chief Ferdinand Silcox had been considering an expansive wilderness “as a memorial to Bob Marshall,” but then Silcox too died. A double blow.

Conservationists like Yard and Clark wrote letters and held meetings. They wanted strong lines on maps that would protect scenic values and restrict certain destructive commercial activities. They practiced dedicated urgency.

Government foresters like Granger wrote letters and held meetings. They wanted strong lines on maps that would allow flexibility to meet many constituents’ needs. They practiced studied deliberation.

In the North Cascades, in 1940, the sides reached an impasse that kept the potential mine within a protected zone, at least temporarily. But the war came to the United States, and war makes quick work of strong lines.

In the fall of 1942, less than a year into the United States’ entry to WWII, a district engineer with the Bureau of Mines requested that the Forest Service approve a road to mines then being explored at Miners Ridge. Copper, molybdenum, and some silver and gold awaited extraction. The engineer estimated that an investment of a mere $5.5 million would be enough to develop a viable operation. Profits could be squeezed out of the rocks within three years.

But the profit motive wasn’t driving the request, the war was.

The Forest Service’s regional forester out of Portland, Lyle Watts who would later become Chief, felt “decidedly heavy pressure” from the mining interests in government and from the Hanna Mining Company. While Watts was ready to allow the road, the acting chief in Washington D.C. tapped the brakes.

The acting chief, Earle Clapp, felt torn because the road “would bisect an area of national-forest land which is of such superlative natural and scenic interest and recreational opportunity that its classification as a wilderness area” excluded the use of motor vehicles. Not only that, but conservation groups, like the Wilderness Society and the Mountaineers, had been assured by the Forest Service that no road would be approved until “the subject had been presented to and discussed” with them. Clapp had an obligation.

This consideration was notable and suggested a desire for workable relationships.

But no one denied that the war had changed everything. Pre-war agreements that might damage “national welfare and security” might be dispensed with, but before that, Clapp wanted to be “definitely assured” that the copper and molybdenum would meet war needs in time and that the Miners Ridge deposits were both indispensable to the war and practicable to obtain. Only after being convinced of that necessity would Clapp allow the “almost irreparable impairment of one of the few remaining wild areas” left.

It turned out that Clapp was convinced easily. Two more letters was enough.

However, the Forest Service did not leave conservationists in the dark. Foresters wrote to Yard and Clark not only informing them of the approval for the road and the plan for the mine but also expressing reluctance to allow what Watts characterized as an invasion of wilderness. Opposing it, in the context of the war, “would be difficult to justify,” Granger told Yard. The wilderness lovers regretted the decision but did not protest.

They did, however, keep tabs. Clark especially stayed up to date, periodically writing the Forest Service for updates. Above a scrawled signature, Clark questioned the agency in 1943: “Will you kindly advise me whether this road has been built and whether it is now in use?”

The project had been canceled without explanation. But what is canceled can be resumed, so in July 1945, after victory in Europe but a month before atomic weapons ended the Pacific war, Clark asked again.

The regional forester, now H. J. Andrews, was happy to inform Clark that the project had been abandoned. “The established wilderness, wild and primitive areas in this Region are coming through the war in good shape if the situation to date may be taken as an indication of things to come,” Andrews said.

No invasion of wilderness had occurred, even in the face of war and total mobilization.

Many more tests would come for this spot of land, deep in the wild, holding treasures.

Comments ()